Description

Continuing the lyric investigations of her first two books, Karla Kelsey’s A Conjoined Book hinges together two new volumes—Aftermath and Become Tree, Become Bird—to create a meditation on the nature of aboutness. Unfolding after an unnamed ecological and emotional fracture, Aftermath’s phrases and imagery layer, the “I” of the poems imagines herself at times into a “she,” a landscape of rift dividing the self from the self as factual moments of languaged perception weave into remembered fictions. The second book, Become Tree, Become Bird grafts the Brothers Grimm’s The Juniper Tree onto the body of Aftermath, naming fracture’s loss and reworking what has splintered into a variation of the fairy tale. Throughout A Conjoined Book, Kelsey’s condensed imagery, shifting points of view, and interweaving formal structures set the spaces between lyric and narrative a-shimmer.

A Conjoined Book is made of close-fitting, intimate poems and adroitly plays the tension between taut compression and leisurely sculpted prose. What is the relation between mind and tree, place and person? How is weather internal? A speaker linked to foliage may double over as a flower fades. Karla Kelsey fully apprehends the delicate relation between fragility and connectivity. She can translate a landscape into interior demise. She can draw for you a map, linking the alphabet of image to that of afterimage. She spells loss in “feather” and “lily.” Kelsey is a writer who can deftly “ply the narrative out at acute angles.” She conjures “music” from a mouth “tipped on a tongue of arrows.”

Laynie Browne, author of Roseate, Points of Gold

This conjoined book—these coordinating clauses—maps in structure and theme the essentially gothic architecture of affect. Which is to say: of reading itself. I couldn’t put it down. “…the reader always changes.” Pass it on.

Christian Hawkey, author of Ventrakl

“In answer to impossible questions I borrow the story of bones burned.” In this astonishing and carefully structured “double book” Karla Kelsey interweaves an extensive mediation on The Juniper Tree with a lyric exploration of trauma, violence, and memory. There is no way to have one without the other: cultural artifact, individual story—Kelsey shows us how these realms are not divisible. Meanwhile, ongoing meditations on aesthetics and “the color sphere,” on folklore, literature, and performance, on the physics of shale gas are blended with astounding elegance. This incredible act of telling builds with a slow burn reminiscent of crime novels–suspenseful, shocking: affects we rarely encounter in books of poetry. But this is not just “poetry” – I’m tempted to say this is all genres, all I’ve encountered and all I’ve never imagined. Horror, elegy, mystery, fairy tale, lyric, treatise, fragment meet one another with all their various intensities of emotion and intellect. Works of this much intelligence, this much care, this much affective presence are rare. I’ve never read anything like it and it’s changed me.

Julie Carr, author of Rag

About the Author

Reviews

Excerpt

Karla Kelsey’s first book, Knowledge, Forms, the Aviary was selected by Carolyn Forché for the 2005 Ahsahta Press Sawtooth Poetry Prize. Iteration Nets, her second book, was published by Ahsahta in 2010. She edits & writes for The Constant Critic, &, with Aaron McCollough, co-directs SplitLevel Texts. A graduate of UCLA, the Iowa Writer’s Workshop, & the University of Denver, Karla is a recipient of a Fulbright lectureship. She has taught creative writing and American literature at the Eötvös Loránd University and at the Eötvös Collegium, both in Budapest, and specializes in poetry at Susquehanna University in Selinsgrove, Pennsylvania.

A brief interview with Karla Kelsey

(conducted by Rusty Morrison)

Here in this text are two books that are so inextricably intertwined. There are so many ways in which each one complicates, compliments, interrogates, intervenes in the other! Can you speak to how this project came about? and then some of the ways the subjects engage each other?

When, in 2006, I moved to Central Pennsylvania, I never had lived so far east, nor had I—a native of Southern California—ever lived in such a rural area. What struck me first was the enormous beauty of the landscape: all trees and river, I felt I was living inside an emerald. Then I began to learn the environmental trauma the landscape had suffered, and still suffers, from the legacies and traditions of mining, lumbering, and now fracking. Also: there are contradictions in such places where the wide, slow Susquehanna runs idyllically along small farms—but between river and farm container trucks zoom past both Amish horse and buggies and adult bookstores. At one point near Harrisburg the road crests through rounded green hills to a view of Three Mile Island. The first book, Aftermath, seeps in this landscape, foregrounding the embodied experience of beauty and rend. There is catastrophe under-tremmoring this book, but it remains unnamed.

After writing Aftermath I thought: what if the catastrophe were to be named? What, then, would happen to the language that I have on the page? How would it curve to an “aboutness?” The Grimm brothers’ tale, “The Juniper Tree”—wherein a stepmother kills her step-son and allows her daughter to take the blame—intrigued me because of its savageness, because of its questions of guilt and responsibility. Also, the boy’s bones, buried under the same juniper tree that shades his birth-mother’s grave, transform into a bird that avenges his death—an intriguing metamorphosis of innocence into the agency of the natural.

I re-worked Aftermath around this tale with the intention of revision, but in the end I found that I had written a second book, Become Tree, Become Bird. A handful of friends were kind enough to read the two different books and to offer their opinion on which book was stronger. G.C. Waldrep, who shares this Central Pennsylvania landscape, suggested that I put them together. Instantly I loved this idea, for it would foreground what happens when narrative is introduced to landscape and embodied experience. The project became A Conjoined Book.

The unnamed ecological crisis looms large in the first book, and then the human failing of the fable’s mother character looms large in the second. Was this an intuitive choice? I’m imagining that the concepts of crisis and cause/effect are ‘at play’ here and shift for you between the two books as a result of this. The concepts of destiny, of fate, seem at play, especially in the second book’s reflections on storytelling fables and folklore. I’m wondering if you can speak to these larger themes and their appearances in the text?

This particular coupling of ecological crisis and the fable mother’s human failing was, on many levels, intuitive. In an early version of Aftermath I had fragments that suggested to me a submerged narrative of a child’s death: “the white square of silence/ the push and the sunk like a stone.” I realized that the narrative suggestion was available only to my mind and wanted to keep it so, in Aftermath, rather than creating a through-line of story. I was interested in asking landscape and pattern to bear and unfold affective states rather than the solid-state emotionality of narrative. I felt the particulars of a physical sense of loss were more important to the book than creating a narrative drama. But because this early, private figuring of loss-as-child was something that I thought quite a bit about (and ultimately rejected as a structure for Aftermath), the decision to use “The Juniper Tree” feels pre-figured, pre-determined, perhaps fated, by this early draft.

The phrase “the white square of silence/ the push and the sunk like a stone” no longer appears in either of the texts, but when I think the words I am transported to a one-lane bridge over part of the Susquehanna, to standing on the bridge in winter, the smell of snow on water and the metal of the bridge rusting through paint; these physical sensations are conjoined with a feeling of irretrievable loss. This landscape and sense create AFTERMATH. Such moments of deep embodied feeling are sometimes caused by events, but are not encapsulated by the autobiographical—are not explained by an individual story of cause and effect. But storytelling forms, such as the folklore underlying Become Tree, Become Bird, create vehicles for telling fleeting, visceral moments so that we can distill them, transfer them into a social form that allows for an experience beyond personal narrative.

At the same time that such vehicles create story, such forms as fable and fairy tale confront us with the fact of all narrative’s untellable and ever-changing components. In many ways “The Juniper Tree” is about the breakdown of story: the step-mother, instead of accepting the narrative in which she has killed her son, allows her daughter Marlene to conclude that she herself has killed her brother. But she also tells Marlene that this is a story that cannot be told. It isn’t until the bones of the boy transform into a bird, who performs the story in song and deed—not as linear plot—that the story forces its way out. And the tale itself exists as something that has been told and retold—and that has shifted in its telling. Become Tree, Become Bird is such a shifting, a re-telling both of Aftermath and “The Juniper Tree.” We seem to be fated to certain forms—think Vladimir Propp (to whom this book is deeply indebted) and his irreducible narrative elements—but we are also fated to never inhabit the same form in the exact same way.

You engage many questions of aesthetics using a deft exploratory lyric approach. Can you speak to your decisions regarding how and why this material came into the text. Can you discuss how you brought them to such elegant fruition? How do you see these concepts in conversation? poems/pages do you recall as being the most vexing to complete?

A Conjoined Book owes itself to process. The book began via a narrowing of approach: Aftermath rejects narrative and concept in order to foreground landscape and pattern. Become Tree, Become Bird began by grafting, quite literally, fragments of narrative onto Aftermath. A Conjoined Book required deep editing of both books: mere repetition of passages from Aftermath through the story of Become Tree, Become Bird was not enough. Talking with Rusty Morrison about the manuscript was essential to realizing that aspects of both texts could be further translated, modified, and scaled back. Through such revision Become Tree, Become Bird in particular opened to other genres: formalist theory, feminist theory, color theory, optics, biography, geology. The more I wrote into each volume, the more they gained individual strength and the more they began talking back and forth with each other.

One of the most exciting moments of working on later drafts of the book was when I realized that I needed to create new “Shadow” components of the “Shadow/Source” poems in Become Tree, Become Bird. The “Shadows” that I had were fairly straightforward repetitions of language from AFTERMATH. Into these moments I worked a little fragmented narrative that I had written the previous season in Budapest—a place with an entirely different physical and emotional landscape for me than the Pennsylvania of A Conjoined Book. In working this narrative into Become Tree, Become Bird, I felt I had discovered a true, symbolic version of the “unnamed” event catalyzing AFTERMATH. In this way, what helps to complete the “Shadows” of the second book is key to the mysterious conditions that set in motion the first book.

Would you tell me a bit about yourself? Anything about you that is not in the bio printed in the book, and that might give insight into your more personal relationship to this text?

I hope that my thoughts, above, on process, landscape, and embodiment speak to my personal relationship to the text. Living with the text and working and re-working so intensely for so long has allowed it to imprint and form me, just as I have imprinted and formed it.

Who are the authors with whom you feel a kinship? who are you reading currently?

The “Source” page of A Conjoined Book lists kinship authors particular to this project—authors who layer the work, and but for these authors the book would not exist. Always I feel I am writing with and between Sylvia Plath and Lyn Hejinian. Rosmarie Waldrop, Mei-mei Berssenbrugge, and Cole Swensen; Donna Stonecipher, Laynie Browne, and Danielle Dutton are writers always important to me and particularly inform this book.

Currently I am working on a project that has me reading in three veins: architecture/ornament, empathy, and imaginative work with a focus on Central/Eastern Europe. On architecture and ornament I read: When Buildings Speak by Anthony Alofsin, Owne Jones’s The Grammar of Ornament, Oleg Grabar’s The Intermediary of Architecture, and Mariusz Czepezynski Cultural Landscapes of Post-Socialist Cities. Anything by Neil Leach and Beatriz Colomina. On empathy I’m reading The Transmission of Affect by Teresa Brennan and Empathy: Philosophical and Psychological Perspectives. Imaginative work that I’m reading includes the Romanian authors Mircea C?rt?rescu’s Blinding, and Nichita St?nescu’s Wheel With a Single Spoke.

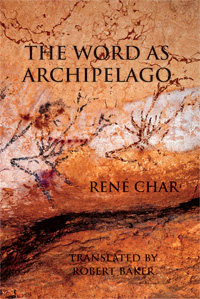

You chose the image that is used in the cover design for this book. Can you talk about your reasons for your choice?

“Moss” is by Ashley Lamb, a multimedia artist who I met in 2007 when she was in Central Pennsylvania for a residency. At first sight I loved Ashley’s collages and have collaborated with her on a series of handmade chapbooks that we created for Kate Greenstreet’s work. Ashley made 40 or 50 small collages that I framed with textured wallpaper and hand-bound into covers for the books. When Omnidawn asked me about a cover image I instantly thought of Ashley’s work. I sent her the manuscript and she sent back to me “Moss” which corresponds so wonderfully with A Conjoined Book: the birds in the upper left-hand cover in cut-out, the two figures in the foreground telling the tale, the green moss overtaking the image from the right. A wonderful Klimt in the Philadelphia Museum of Art gave me the idea for using a textile pattern to back the collage. Cassandra Smith knew exactly the sort of design to try and masterfully connected all of the pieces of the cover into a fantastic whole that speaks to the book’s world of landscape, imagination, and pattern.

… in surrendering to the powerful crosscurrents of the multiple stories, one is struck most by Kelsey’s impressive layering and her ability to navigate the reader through disparate registers of allusion and disjunctive settings in time. These are leaps that open up the land around us, and remind us that we are, simultaneously, creatures of now and then, heroes and anti-heroes of overlapping stories.

For A Conjoined Book, what might Kelsey see as the relationship between her work and her readers? Is it a grafting, so that reader and poem should feel intertwined in sentiment? Is it poem as proposition, where the reader is asked to navigate the lyrical logic? That I feel compelled to these questions when reading Kelsey’s work is what has established me as one of her truly devoted readers. A Conjoined Book only further adds to that sentiment.

Drawing from folklore and varations on the Grimm tale of The Juniper Tree, these explorations show transfiguration in many lights: through the painterly technique of “cangiante” (“a painter’s changing to a different, lighter hue when the original hue cannot be made light enough”); through mythic grief and “the split place of its purpled heart”; through live reading of the “bluing through / the river of / the book,” in which “feathers cover / my eyes.” A reader’s eyes should feather similarly.

Given that she has titled the first work “AFTERMATH,” and the second section includes a poem such as “Afterimages:” and the series of poems titled “Interstitial Weather Remnant:,” it is as though Kelsey focuses her gaze throughout the two works on what remains after a particular event, whether a trauma, devastation or storm. She writes out the remnants themselves, using the scattered, disparate pieces to shape together into something coherent, complex and remarkably solid.

from Aftermath

I awake mid-

thought & feeling

the bed sheets taut

I lily over-

rained

& burgeoning. This season

of metal left to rust,

the house closed up

& emptying down

the gravel walk

Facets shine off the river & the character appears in her robe stitched with

peacock eyes, skilled in grasping what her mother meant when she said now

this is your life & so you live it. But what is it that she’s looking for, miming the

gesture of a pair of doves gone home to the cote

*

from Become Tree, Become Bird

Down bird

down sky

down jet-

jet whirring

covered in birds

I saw salt.

I saw with eyes

of salt hard by

the herd

wading shallows

like the tilling moon

rose & set

& rose

out of long grass

to cure the sky

struck in

vapor trails.

No nest here.

No downy feather.

No bed.

No rest.