Description

Winner of the 2015 Omnidawn 1st/2nd Poetry Book Prize

Selected by Claudia Rankine

HOUSE A investigates the tones and textures of immigrant home-building by asking: How is the body inscribed with a cosmology of home, and vice versa? An assemblage of oblique letters to Mao, “dream-geometry” poems, and image-text experiments, this debut book of poetry seeks to render not facts but the feeling of a childhood household whose structures are simultaneously haunted and buoyed by ghosts of history that blur with a constellation of sheltering figures, patterns, and shadows. With evocative and intellectual precision, HOUSE A weaves personal, discursive, and lyrical textures to invoke the immersive-obscured experience of an immigrant home’s entanglement while mapping a new poetics of American Home, steeped in longing and rooted by displacement.

Jennifer S. Cheng’s House A is an exquisite exploration of the ability of diasporic longing to live within a continuous and full life. These tender epistolary prose poems embody the constant sense of dislocation for the immigrant, while redefining affiliation nonetheless. The poems, addressed to “Dear Mao” in the first section, weave, correct and redirect. They chronicle, in the alphabetically-organized second section, and instruct on “How to Build an American Home” in the third section, in order to make apparent the illusive tone and mood of an upbringing—its porousness relative to history, myth and location. Not since Michael Ondaatje’s Running in the Family and Calvino’s invisible Cities have I encountered such attention to the construction of love and love’s capacity to transform unimagined locations.

Claudia Rankine, judge of the 2015 Omnidawn 1st/2nd Poetry Book Contest

In Jennifer S. Cheng’s House A the susurration of the tides pull at the posts that make a home, or at least the idea of home. A wound is a dwelling place. The smells of cooking, the sticky warmth of Texas summers, and the blueprints that map the human heart attempt elegies superimposed against the doors of childhood. Cheng deftly juxtaposes the world and the word in an intimate meditation on space and reverie, ultimately understanding that “. . . before language . . . children experience memories as image and sound, which is to say they experience them as poetry.” House A is radiant.

Oliver de la Paz, author of Post Subject: A Fable

In Jennifer S. Cheng’s House A we find an intelligence so deep it feels primal, a sensory perception so acute it links us to the phases of the moon, the tidal patterns of the ocean, the movements beneath the earth’s surface, a tremulous upheaval which becomes a kind of knowing. Cheng shows us that this knowing is akin to a child’s—the child beneath the kitchen table, the child attuned not to language, or fact, or even story, but to atmosphere, spinning her web of silken presences at the juncture of the table leg. Family (and history) here is echo, heartbeat, windows and doors being opened, shadow and sunlight on the floors and walls—the texture of being cared for. Cheng’s poems paradoxically, beautifully, become the tools of a super-fine archaeology which unearths the foundations of our (almost) lost dwelling places before language—for in these poems sensation and instinct are at once elemental and as eloquent as the flight of migratory birds. How can it be that the history of a particular American immigrant family takes us to such earthly origins? Well, we have to keep reading Cheng’s poems with their atmospheric disjunctions, their rhetorical precisions that cut into and refine, that scrape back and debride the cells of home building (nest and hive and shell), that take their microscopically thin samplings, in order to find out.

Barbara Tomash, author of Arboreal

Addendum to acknowledgments: poems from this book also originally appeared in The Margins (AAWW) and Waxwing.

About the Author

Reviews

Excerpt

Jennifer S. Cheng is a poet and essayist with MFA degrees from the University of Iowa and San Francisco State University and a BA from Brown University. A US Fulbright scholar, Kundiman fellow, and Pushcart Prize nominee, she is the author of an image-text chapbook, Invocation: An Essay (New Michigan Press), and her writing appears in Tin House, AGNI, Mid-American Review, DIAGRAM, Tarpaulin Sky, The Volta and elsewhere. Having grown up in Texas, Hong Kong, and Connecticut, she currently lives in San Francisco. www.jenniferscheng.com.

A brief interview with Jennifer S. Cheng

conducted by Rusty Morrison

It is such a great pleasure for all of the poetry editors at Omnidawn that Claudia Rankine selected HOUSE A as the winner of our 1st/2nd Book Prize. As one of the blind readers who screens work for this and for all of our poetry contests, I recall my delight to see this manuscript in the blind submissions. I immediately recognized that this work had come to us before, in shorter form, through our chapbook contest. It had not won, yet I knew it to be an amazing work in chapbook form. Then reading it for this contest, I was stunned by the power of HOUSE A, and all that is included now in this text as a full book. Would you speak to the ways that the sections cohere, and how you made decisions to bring the text together in this form?

Inside the book, there are: migratory birds, (un)tethered boats, water, sleep, the body in dislocation, shadows, mappings, weather systems, echolocation, nests, moons. Which is to say that all of our work as writers and artists are like maps of our obsessions, our preoccupations, our hauntings. I started writing “Letters to Mao” in summer months, and most of the prose poems in that series came quickly (which rarely happens for me; I am usually slow like a snail). I work mostly by intuition, and it made sense to me that other poems I subsequently wrote—those in the sequence “House A; Geometry B” and the series “How to Build an American Home”—were of a similar attunement and investigation. Maybe I can call it the poetics of an immigrant home: how the body is inscribed with a cosmology of home and vice versa. How, for example, are the subtleties of history, displacement, and migration woven into the shelter my parents made for me and my siblings? In all three sections, I am writing into a critical and personal silence, and I hope that by evoking the shadows and subterranean, I complicate the immigrant landscape, conjure the small layers it can carry.

Although the three sections all circle the same center, the first part operates by way of water and sleep, whereas the other two carry more angles and earth; there is tension, which I like. I like the idea of the three parts being sewn together. Each stands alone, but in stitching them under the same roof, in choosing to lay down those boundaries, I am constructing another little dwelling with multiple rooms; a knitted constellation; a map with limbs. Or I might think of them as various transparencies I am overlaying on one another, different textu(r)al representations of the same space. Barthes has a theory of fragments that captions all of my work as a writer (I quote it everywhere), and it relates to this book of poems as well: the fragments are then so many stones on the perimeter of a circle.

I want to focus this question on the first section, its power, lyric strengths, its complexity. I would be grateful if you could speak to the ‘character’ of Mao in this work, and to the child as speaking agent who creates an epistolary relationship with him. I’m impressed by how masterfully the character of Mao stands for so much that is ineffable, so much that permeates the child’s life without her conscious understanding. Yet, too, the figure stands for very real cultural norms. For me, he becomes both cipher and barometer of the weather of the child’s experience. Please talk about this section in whatever ways you’d like, but I would be grateful to hear what brought you to envision this? What was most challenging in this enactment?

Ineffable is the right word! In my addresses to Mao, I am trying to get at something I will never be able to articulate outright—it has to do with the ineffability of childhood, and of History in an immigrant household; the ineffability of Mao as a figure, both objectively and personally to me; the ineffability of home and longing for home. Sometimes the pronoun he/him is startling because, growing up, my conception of Mao was never quite as a man or person. Maybe that’s why it felt subversive to write letters to him. He was a specter, a tenor that drifted in and out, vague but formidable background sounds to my childhood, like white noise. My parents would only ever speak his name in conjunction with evil, and I accumulated splinters of memories and images: bodies floating in the river, meals of porridge to stretch out hunger, decades apart from a parent or spouse or siblings. Our household is not one of personal stories or explicit communication, so it was all behind a veil; yet I cannot remember a time when I didn’t know who he was, his name so entangled with my family’s history, the trajectory of where my parents came from and how I came to exist as a child in America. It’s strange and complicating for a name/face/symbol so abhorrent and expansive to feel simultaneously intimate.

What does it mean for Mao and Home to be intertwined in such complex and ambiguous ways—for him to be part of the atmosphere, as much as the sounds of an airplane in the sky or sun on a curtain? How do I explain how History is like water in my house, permeating yet impossible to parse or boundary: simultaneously intimate and distant, known and unknown, bulky and infinitesimal? It touches everything yet is slippery and unreliable. There is an odd impulse to look Mao in the face and justify, explain, defy, incriminate, complicate… Maybe it is a need to summon rather than unravel this elusive and powerful ghost; maybe it is a need to announce my sense of identity/home—always partially adrift—to someone who is partly responsible for it and will never actually hear me.

There is a way in which second-generation children are constantly reconciling outside/inside spheres, like the Mao in U.S. consciousness and the Mao in my house. While writing these poems, I was thinking about this tension and how the body unconsciously absorbs the years of war, famine, fear, and separation in inexplicable ways. Where in the house is it located—in the lamplight, the placement of objects, movements of bodies? I am interested in the interactions of histories in a household: personal history, family history, and History. Intersection implies a point, but this is more like ocean waves meeting, a convergence of tenderness, loss, protection, vigilance, rootedness and unrootedness. The ocean emerges as a metaphor and guiding rhythm: “And if water is a metaphor, then it is because water fills up a room, slow-moving, blurry, immersive but obscured.”

I’m fascinated by this text’s use of the child’s experience as fulcrum to explore our very human need to understand our relationship to place, to the spaces we occupy, and to the materials within them and their myriad meanings. I’m excited by the ways that this text demonstrates formally—ie, in many of your formal strategies—the subtleties of our relations to space, the ways we design and determine the spaces we occupy. I’m interested in your discussing your process of bringing images into direct relation with language to heighten their impact and hone their suggestive force, your use of the alphabet, and by all the ways that you reflect and refract meanings of “house” and “home.” I’d like to ask you to speak of place and how this text is a meditation on the personalizing and socializing of space, as reflected in both form and content. To do so, you might focus on particular poems or segments that were especially challenging to you, or especially provocative for you, as you attempted to bring your intuitions to the page.

While writing this book, I kept returning to the question: How does our inhabitation and navigation of space become a map that we internalize from childhood? In graduate school I audited a class called Archaeology of Anthropology and learned about ancient caves that were composed by people to reflect their cosmology. It made me think how in a way all our homes are like this. After the class was over, I read anthropology papers on the relationship between body and space and how this connects to one’s sense of home and self. I collected textures and images of houses and geometries.

There is something beautiful and truthful about the (im)precision of charting something that is by nature intangible and murky. You can only approach it poetically.

“House A; Geometry B” undertakes this by entering a language of “dream geometry,” which comes from Gaston Bachelard’s Poetics of Space, a miraculous book that is simultaneously poetic phenomenology and architecture theory. I can say about this section: It is like a framework, a grid shoring up the topography of the book. The shape of the text is long and rectangular, but also important is the spread of space so that angles are perforated with air. The alphabet as a way of accretion reflects the structures of indices or schematics and also the incantation of childhood learning. Inside are weather systems suspended in hallways, vectors embroidered onto walls, and these early lines: “we build a house to locate ourselves; a / body lay in the house, a body lay slant in / the house” and “if we were to say, the father is a convex / polyhedra. or, he lay out the living room / in tetrahedron composed.” All of the refractions and reflections create a prism-like experience that is geometric and echolocaic. We sense how we are constructing through ritual a personal language in order “to map, to constellate, to excavate. a / blueprint for this mythos.”

In the closing series, “How to Build an American Home,” each poem consists of a visual artifact and text. My intention is to play on the notion of instruction and blueprint: to refract it, disrupt it, wrinkle it. I have always loved old diagrams, surveyor photographs, maps—objects that document and delineate—but I am also interested in them as atmosphere or texture, that is, something to experience viscerally, metaphorically, abstractly. Each of the images I include carries a certain wound (Barthes’ punctum) for me in this manner, which informs how the image frames the text and vice versa. I “read” the images as if a wall texture or plant dissection can be instructive; there is something political to me in asserting what is otherwise hidden, peripheral, illegible as legitimized modes of navigation. I didn’t realize this until now, but in all parts of the book I am trying to transform shadows and stains into maps, and here I approach it literally. Indeed, on a larger level my intent is to redefine the blueprint for what an “American Home” means, to blur its boundaries and measurements.

Are there authors, photographers, artists, musicians, or workers in any field of creative endeavor, with whom you have felt and still feel most kinship? Whose works have stayed most relevant to you as a poet and thinker? Are there any whose work is especially relevant to this text? I very much appreciated the quotes that begin this text, from J. Tanizaki

In making for ourselves a place to live,

we first spread a parasol to throw a shadow on the earth,

and in the pale light of the shadow we put together a house.

And, not surprisingly, G. Bachelard, whose work wonderfully ghosts your text:

Our house is our corner of the world…

It is our first universe, a real cosmos.

Please feel free answer whatever aspects of this question your intuitions bring to mind.

In the middle of this project I started reading Poetics of Space purely by chance for a class with poet-artist Truong Tran, and I felt an immediate and intense recognition; it was electrifying, overwhelming, and like coming home. So many phrases and sentences were exactly what I was doing! My copy of the book is ridiculous—it has fifty-two page markers sticking out and looks like a centipede.

Similarly In Praise of Shadows has always been important to my writing and being. I feel such closeness with shadows, and it represents many things to me that layer into the book: it is an aesthetics of murkiness and imperfection; it is protection and safety; it is hiddenness and periphery; it is ephemeral, elusive, something half-evaporated and faraway. I am currently reading a book in which Rebecca Solnit describes longing as an experience in itself, and she says this is why sadness is sometimes beautiful—something is always still far away. I think this is why I am drawn to shadows. Something is literally lost or obscured, but in its place is a tone and texture of fullness unto its own. What does it mean to build a house here? Interestingly, Tanizaki speculates there is a distinctive relationship between Asian cultures and shadows—we accepted the darkness we found ourselves in and so immersed ourselves in it.

Outside the literary, I like installation art that construct experiential spaces for the body, like Cybele Lyle’s, who I recently discovered at an open studio and then later realized describes her work with: “explore the unknown by building multiple architectures and rooms within rooms.” She also had black-and-white photography prints that she was painting over in thick streaks of color, loosely, so ocean and terrain peeked out in places. At the Guggenheim I loved the side exhibit Photo-Poetics with Leslie Hewitt, who layers photographs over documents. I am obsessed with the work of Christine Sun Kim, a deaf artist who translates sound in miraculous ways, redefining the concept in her own terms.

I always hold these writers in the shade of my heart: Marilynne Robinson, Anne Carson, Fanny Howe (especially “Bewilderment”), James Agee, Theresa Hak Kyung Cha, Jenny Boully, Mei-Mei Berssenbrugge, and of course Claudia Rankine (for my first book to be selected by a hero sent me over the moon). Books/essays/poems that are currently my night sky: Post Subject: A Fable by Oliver de la Paz, Silent Anatomies by Monica Ong, Night Sky with Exit Wound by Ocean Vuong, Spit by Esther Lee, April Freely’s mini-essay on the Voyager Golden Record, “Mooncalf” by Shamala Gallagher, “And the Place was Matter” by Jane Wong, “Life of a Drowning” by Muriel Leung, Sueyeun Juliette Lee’s videopoems. This is leaving out many.

Would you tell me a bit about yourself? Anything you are willing to share that might not be in your short bio that is published in the book? Anything that might have interesting, tangential relation to the book?, or anything that doesn’t!

1) When I first began writing, it was because my undergraduate teacher Catherine Imbriglio introduced the lyric essay to me, and it was like finding a language I didn’t know existed, yet for which I had been searching my entire life. I still think of my poems as tiny essays: there are little arguments toward truth being made inside. There are also silences, holes, moments of opacity, which I think are just as truthful. I recently wrote “Dear Blank Space: A Literacy Narrative” for Entropy on the poetics and politics of silence, unknowability, wilderness, the margins, and broken things. My kinship with the lyric essay: how I am compelled toward both precision and wilderness, how the need to be known is matched by a need to be alone (the latter concept comes from an essay on Virginia Woolf by Joshua Rothman).

2) My family moved around growing up, so I was always losing things: little toys made of paper, drawings, prized pencils. Also: my sense of belonging, the feeling of familiarity. Maybe that’s why I have trouble throwing things away and why I always feel like things are slipping between my fingers, about to be lost.

3) The creature I feel most akin to is the jellyfish because of its slow and muted rhythms. It moves mostly by the sea’s currents. It casts a net of nerves.

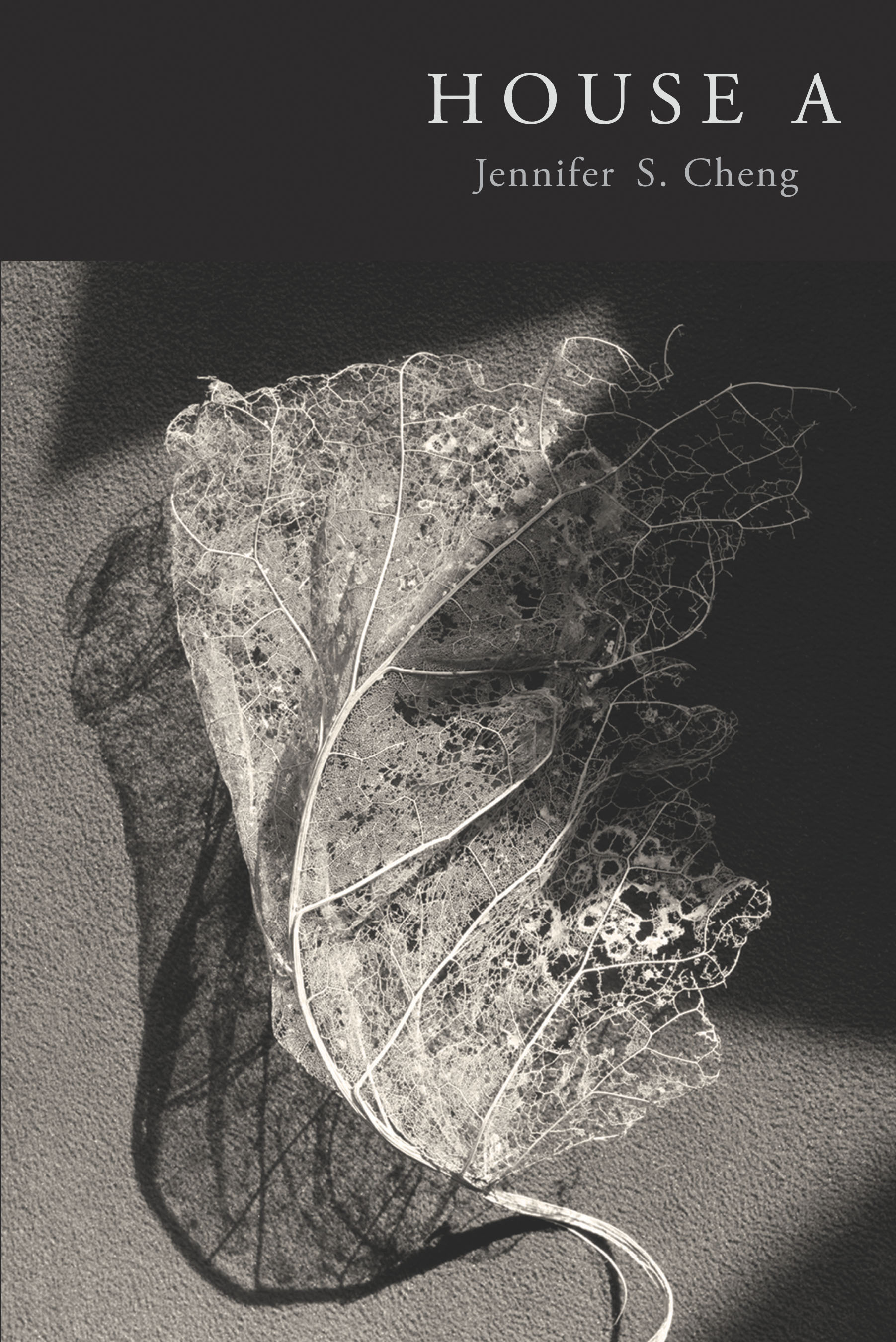

You selected the art for the cover design for this book. Would you describe your relationship to the photograph you selected, and what you envisioned as cover design for this text?

Occasionally my partner and I go to a local darkroom to process and print black-and-white film. I love the quietness and ritual of it, all those bodies moving in the dark. He kept mentioning the work of a fellow member, and when I finally took notice, they were astonishing enlarged prints of half-disintegrated leaves: the veins were map-like, fragile, and stark. In a moment of courage I emailed the artist, who turned out to be a very kind older man named Mitsu Yoshikawa. He told me his process: he finds leaves that have been eaten through by insects and weather, washes them gently with water, and places them against a heavy cloth.

In her elegiac debut, Cheng, winner of the 2015 Omnidawn 1st/2nd Book Prize, excavates the nostalgic ephemera of the immigrant home. The poems are delicate and dexterous, with Cheng juxtaposing diasporic history with childhood memory.

?”‘Geometry,’ writes poet and essayist Jennifer S. Cheng in her 2016 poetry collection House A, ‘is a configuration of parts, each asking itself: How do I adhere?” It is question that reverberates throughout the book’s three sections, a question asked out of the experience of growing up in an immigrant home, immersed in an ‘alien’ language and culture, a home built on displacement and longing. Cheng’s poems, which shift between verse and prose, are at once airy and anchoring, precise and dreamlike, intellectual and intuitive, strange and familiar, maps to nowhere. House A is both ineffable, a ghost house, a kind of template, as well as House A, ‘A’ as in America, our large and complicated home.?”

A poetry collection constructed from three disparate yet harmonious parts, House A concerns itself with identity-building, diaspora, and the physical act of building a home and an immigrant family on foreign soil. Yet while these are familiar themes, Cheng defamiliarizes them for the reader through her refractory poems that have the effect of a kaleidoscope, dividing experiences into tiny crystalline slivers and re-assembling them to illustrate the unexpected colors and shapes that lie buried within everyday domestic life.

House A, her first full-length collection of poems, shows us the “chaos and wholeness” of a voice that is sedimented with its own past, even in the most personal moments of lyric address. Indeed, the speaker’s lexicon is revealed as being at once mediated and insular, a social construct that ultimately isolates. ‘We each live within our own language,’ Cheng explains, and any closeness, any true connection requires “stitching these languages together.” Yet speech is not as simple as the relationship between signifier and signified. Rather, Cheng reminds us that the larger structures of power and authority that surround us are embedded, and enacted, within our smallest grammatical choices.

The precocious [Letters to Mao] combine references to neuropsychological theories of sleep with tender memories of a parent’s cooking or storytelling. They also play with our logical expectations, which is fitting, since these poems grant access to the truth of daydreams, not waking reason.

At its best moments, it gets to the heart of the immigrant experience, tapping into the suspicion that perhaps the whole earth is no natural home, that everyone builds their home one way or another. This is what many want to forget, especially as the world grapples with immigrant and refugee issues.

House A inherits many tropes from the essay, especially its more formal, intellectual rhetoric, but the writing’s movement is more liquid, more ruminative. Where an essay might position itself as an argument, a procession of points that builds on itself through causality—if this then that—Cheng’s writing is more like the immigrant’s decentered network, a collection of and’s and or’s that are too intimate, too contradictory to build up to something as singular and definitive as a thesis. Just like Cheng’s concept of home, the essay is a structure too rigid to house her experience, but one that has defined it nonetheless. It’s an institution to be cherished and subverted, sometimes in the same breath.

I want to describe for you the feeling of sleep, as described by neuropsychologist Giulio Tononi, who uses words like oscillations and waves, while his patient is noted to gather the phrase the sea moving a boat. Elsewhere are words like sleepwalking and daydreaming, so I can only conclude that sleep is a boundary whose line is slowly eroding. Sleep, like childhood, is more of a sense than an experience we can articulate from beginning to end. As a child in Texas bathed in sun, I often fell asleep in the car, even in daytime, and my father would carry me into the house with my head pressed against his shoulder. If my mother, who is much smaller, was the driver, she would crack open a window on warm afternoons, and I would later wake to the pleasure of utter silence and aloneness, the sun across my face. I want to emphasize to you that both responses were acts of love, and if by chance an airplane overhead excavated an echo in the sky, then I knew that I was cradled in its sound. Inside our home of secret languages, my mother boiled up a pot of salty rice porridge and my father watched our neighbors like a devout mockingbird: straw doormats, pine wreaths in the winter. So I want you to know that if sleep is an ocean, then it is because we are migrants inwardly sighing along to its many oscillations, unintimidated by factual distances but awash in the knowledge of three: body, bodying, embodied. And if water is a metaphor, then it is because water fills up a room, slow-moving, blurry, immersive but obscured. Strangely enough, it was not my father but my mother who gave us history lessons steeped in a pale, languorous liquid: we sleep where our home is, and we build a home where we sleep.