Description

Winner of the Omnidawn Open

Selected by Mary Jo Bang

Our Animal hybridizes novel flaking into poetic forms like a gnat swarm, magnetic filings or migratory flux. It’s a fierce inquiry into Othering, tracking Kafka’s life through his deep identification with animals, especially those hunted or outcast. Graphically complex with metamorphic text layers, the chapters shape-shift in relation to crows, dragonflies, a frog; there are deer, swallows, a goldfinch, humans, a hybrid Beast, wolf, Insekt, a small unidentified animal in its burrow. Drawing on family history in Hungary and Siberia, the phonemes of exile and homeland, the familiar and displaced, Our Animal entangles us in biography as biology—bios writing and re-writing wartime, fragments of history and the nature of trans-lation: interlingual, interspecies—paradisiacal transfiguration that leaves out no being.

The continual back and forth movement of this multi-layered, multi-sourced story of literary kinship over time comes to resemble the pacing of a caged bear. The va-et-vient takes place between Stricker and Kafka, as well as between the two them and us, the readers, animals all. As they pace within the enclosure-like poems, the border between what Kafka wrote and what Stricker is writing disolves, and as it does, unattributed fragments rise to the surface out of what appears to be the static of the two talking over one another: “That’s o.k. I show up later anyway” “a stray dog scuffles behind a dumpster” “wants earth” “like a blond wax” “angel Madonna doll.” There are even flashes here and there of what might be taken for truth. Not the old idea of truth, a polished-to-perfection gem, but a Janus-faced truth that resists the falsity of sound-bite reductive purity and edges closer instead to the convulsive beauty of surrealism. In the chaos of any given moment, on the mirror at the back of the cage we can see ourselves looking first here, then there—“I” “a” “wax” “doll”—as we mime Stricker’s search for some consoling likeness.

Mary Jo Bang, judge of the 2014 Omnidawn Open

Our Animal haunts the tragic peripheries of World War II, and in doing so touches upon themes central to Jewish culture and literature after the Shoah: G-d, diaspora, trauma, memory, testimony, history, and survival. Though he died between the wars, it makes sense that Kafka (so close tokavka, the Czech for crow) is Stricker’s companion animal through the landscape of “clotted mud and snow that was wartime,” given his sensibility attuned equally to devastation and transformation, doubt and faith. The brilliance of this book lies in Stricker’s effortless fusion of so many genres—biography, lyric, essay, visual poetry—into a singular idiom while documenting her search for the Soul’s residence after unthinkable disaster. Her ethics is such that the beauty of the writing does not shield us from brutality, instead leading us always “further into the dark conveyance beyond imagination.”

Brian Teare, author of Companion Grasses

In Our Animal we find ourselves driving at nightfall, radio on, away from Dante’s selva oscura, in the direction of Eden. The poems are the broadcast of every instance and new species passed along the way. Fabulously, among these species, Stricker numbers you and I.

Donald Revell, author of ESSAY: A CRITICAL MEMOIR

Meredith Stricker’s chapter-poem is a brilliant mix of lyric, narrative, and epic elements. Sampling, scrambling, overlaying, collaging, and crossing out language from Kafka’s diaries, stories, and aphorisms and Dante’s hell and paradise, Stricker creates a set of meditations in which human, animal, vegetable, and mineral life not only co-exist but converse. What they say in the transition zone the poem creates is spacious and wise, strange but not estranged, and rich in its resonance for our nonhuman moment.

Adalaide Morris, author of How to Live/What to Do: H.D.’s Cultural Poetics

About the Author

Reviews

Excerpt

Meredith Stricker is an artist, designer and poet who has published three collections of poetry involving performance, graphic over-lays and hybrid forms of documentary/lyric. She is co-director of visual poetry collaborative focusing on architecture in Big Sur and projects to bring together artists, writers, musicians and experimental media. She received the National Poetry Series Award and The Iowa Review Poetry Award. Her poetry and visual work has appeared widely including in Conjunctions, Drunken Boat, the Volta, as well as in galleries, museums and performance spaces.

A brief interview with Meredith Stricker

(conducted by Rusty Morrison)

I was delighted when I saw that Mary Jo Bang selected OUR ANIMAL as the winner of the Omnidawn Open Contest. It was a great favorite of mine and a great favorite for a number of the other Omnidawn poetry editors—we are the blind readers for our contests. The scope of the project is unlike any work I’ve read. The lyric intellect amasses both elegy and elation, lament and lumination. I can’t help but quote from the opening poem: “…if not solace, kinship, if not kinship a flash of alienation / in abeyance, breathing space between grassblades and grassblades…” Can you speak to how this manuscript began for you? How your own relationship to the writings of Kafka influenced its inception and then its evolution? and how this work reflects upon a relation to the other, the hunted, the outcast?

Rusty, thanks so much — you’re asking such expansive questions —

Kafka had this extraordinary capacity to absorb, identify with, not turn away from the Other — I was just opened wide by his compassion and willingness to take on qualitiesof being hunted, persecuted — not just from the human, but also the animal, insect perspective — while including unwanted aspects of one’s self. Which means that this identification is never sentimental. It’s not theoretical but something much more risky — visceral and highly embodied, felt through the pores of the skin, sense of smell and touch. He allows in the fallible, the absurd, the embarrassing. The kinds of things I resist and struggle with in my own life.

In my rendering of OUR ANIMAL, many animals shape-shift — they translate themselves into Kafka or myself or the reader or each other. There are crows, a frog, bug, deer, swallows, a goldfinch, humans, a game-bird, worms, a hybrid Machine/Beast, dragonflies, wolves, a small unidentified mammal in a burrow … There’s a sense of a fluidity among species as well as breach.

You were finding your own relationship to Kafka’s work shifting in the process … ?

Yes, I am far from a Kafka scholar, my work is not at all academic — more like an instinctive — possibly obsessive — rummaging about. I would say OUR ANIMAL began from scraps, assembled like found objects while I was reading Kafka’s journals and diaries, particularly The Zürau Aphorisms.

Then Kafka’s days began to thread through my own family history — his world seemed familiar/familial — apprehended in snatches of stories and sepia photographs. As “Displaced Persons”, my mother and her family fled Hungary after WWII (on the same harrowing routes Syrian and North African refugees are now trying to traverse). Members of my father’s family remained in Siberia, stranded for decades in labor camps. I grew up in a disjunctively bright and new California with stories of border crossings in a mix of languages, a milieu of resettled refugees, for whom home was elsewhere and settled security was not felt as a given but more of a precarious construct.

Entering into Kafka’s notes of his days and thoughts, I was moved by how the personal can cross into a wider communal, co-mingled world. Somehow this sense of intimacy and immediacy with odd moments in his life — washing laundry, worrying about his appearance, going to Steinerian healers, Yiddish theater — freed me from my own past reading and clichés of the Kafkaesque — to this entirely new sense of him. It’s as though his life and influence retain their metamorphic capacities outside fame.

At times, you’ve spoken of OUR ANIMAL as a novel. Can you talk about the hybrid aspects of this work?

Opening to Kafka led me to ask: what are the possibilities of poetry/narrative? How do stories tell themselves through us? How does writing change our personal or cultural story? What are the continuities/differences between “prose” and “poetry”?

I’m enthralled by the way fragments re-assemble themselves in us or as us. It feels essential to participate in the jaggedness of narrative and history. I don’t want to create writing separate from living but some kind of lived writing or writing that can change me or a reader. Imagining that the text alters by being read, becomes if not “whole” (which is too abstract, Platonic) — at least re-patched, re-loomed, marked by contact.

You’re speaking about a participatory poetics, how would you describe this re-patching in relation to OUR ANIMAL?

For instance, it wasn’t until I had finished this manuscript, I learned my mother had been an interpreter at Nuremberg working with testimony from Goering and Horthy. This is how parts of our stories surface “out of order” — there really is no beginning, middle and end, but there is perhaps weave we are part of.

In her introduction, Mary Jo Bang speaks of the text of OUR ANIMAL as “machine fabric that’s been taken apart, thread by thread and then rewoven by hand”. Years after my aunt Renate died, I was told how as a girl escaping the chaos of post-war Germany, she hid with her mother and sister in the woods after narrowly not boarding a train that was blown up a few minutes down the tracks. And, as she searched for some solace under the trees, pushing her hands into the leaves, an amber ring fell into her hand. What is that amber ring? How does it return? Later her mother would unravel their sweaters, which they would painstakingly re-knit again and again into different patterns to keep themselves occupied. Here’s something of that weave.

So for me, OUR ANIMAL is also about the “kinship” of reader/writer that both unravels and re-weaves — this mysterious, unmistakable arc across and into another person’s imagining — how our minds become entangled, our cortex over-written — how writing and reading continue each other beyond the personal: “that sense that you were yourself in some way a prefigurement of the passage, stream leading to a small marl lake clotted with lily pads streaked with blue dragonflies a passage that now clarifies or at least reflects you unsteadily in tremulous water that also contains sky

and smudgy willow branches pale-green with the quiet, confident gestures of hands

like islands

that wax and wane”

It is impossible to discuss this work without considering the craft in the structuring of the work. As Adelaide Morris explains in her endorsement each “chapter-poem is a brilliant mix of lyric, narrative, and epic elements. Sampling, scrambling, overlaying, collaging, and crossing out language from Kafka’s diaries, stories, and aphorisms and Dante’s hell and paradise, Stricker creates a set of meditations in which human, animal, vegetable, and mineral life not only co-exist but converse. Rarely does a reader find such complexity of both form and content to be so fully integrated in a work. Can you discuss your relationship to craft: Have you seen yourself change as a writer? Does this manuscript reflect an evolution in your approach to writing? And/or a break in an earlier approach to writing for you?

Well, the work has been immeasurably liberating for me. It just kept Metamorphizing, literally, in every way. I wanted to make a revision of Dante’s Paradiso based on Kafka’s thinking turned into a graphic novel. I was using pages of poem drafts that were accidentally overprinted on the wrong side of scrap paper. At first, there was a lot of visual work: video stills of crows, Kafka’s Father’s large boot, drawings. I felt if Kafka could create a Insekt /human, why not hybrid poem/graphic novel?

This could have been daunting, since I have no idea how to write what could be called fiction. But, I just tried making chapters and prose blocks that are composed like poems. Each page would have a shape, and each line would have its own voice or integrity paying attention to line breaks as with a poem. Then each chapter could find its own form, instead of using pre-set margins typical of a novel.

Bits of poem fragment/phrases began to break away and migrate around the page. This was also very freeing. First: being able to write continuously and then that the words themselves might break out of their fixed positions and create new relationships and voicings. I loved that each chapter be quite different and yet relate to the whole — and that a story could unfold in a kind of fractal collage. I’m excited how there can be a visual rhyme or resonance, as well as aural when these fragments free themselves and roam around the page edges.

I also feel this book is very much a material object. It’s odd but simple — I mean tangible, like piecing disparate actual materials together: found crow feathers, old family photographs, pigments, fabric.

There’s a wildness, I would hope, but also exactitude in this process.

I’d be grateful if you chose a point in the manuscript, perhaps a chapter-poem that has particularly powerful significance for you, or that was especially difficult for you, and then discuss why. What experience or convergence of experiences initiated any particular aspect of this work that might be fruitful to discuss? What did the writing of that part of the manuscript demand of you? Change in you? And/or you might focus upon a poem-chapter in the book that surprised you. Frightened you, in what it demanded from you.

Wow, you bring up being frightened in this process. That is so resonant — you could say fear (or rather the shifting or possible healing of fear) was a close collaborator.

I was humming along, in the midst of writing this book, when I got slammed by waves of panic attacks and the surfacing of trauma from years past. As I returned, shaky, sweating, trembling with Kierkegaardian dread to these pages, there was Gregor awakening from a “traum” while I was in a state described by a trauma specialist as “molten chrysalis” — (apparently the pupa must literally melt in order to reconstitute into the structure of a butterfly or moth).

Which, of course, seemed immediately relevant given Gregor/Insekt’s Metamorphosis. As though he were signaling to me across war- and time zones. This was weirdly reassuring, the sense of the pages reading me before I was at all conscious of their material.

All of the chapters felt impelled by a kind of urgency — and also the release of held energy, as in a thunderstorm. Where the confined is met by spaciousness.

Could you talk about any writers &/or artists &/or thinkers who have influenced you in this work? (in what direct or indirect ways have you felt this occur?) And/or could you talk about who are you reading currently? With whom do you feel a kinship or a provocation or…?

I hadn’t realized it before you asked, but for quite a while now, at home while washing dishes, we’ve reading aloud from Virginia Woolf’s diaries. I now feel the strong effect of her sense of “novel” and “poem” as a kind of continuum.

I was also enlightened by reading Jean-Christophe Bailly’s On the Animal Side, a wondrous collection of essays where he speaks of Kafka’s rare “transference” with animals. As well as by David Abrams’ On Becoming Animal. There were biographies of Kafka by Nicholas Murray and Robert Calasso. Other influences on this process: both the collages and architectonic work of Schwitters; Walter Benjamin’s diaries with numerous collage-like fragments, the accretion of his Arcades Project and Anselm Kiefer’s visual work countering post-war cultural amnesia.

I love reading lists — right now I’m gathering steam and materials for a new work called SENTIENCE about bees, Amazonia, toxic waste. I’m researching tattoos and writing, the Korean DMZ and oral histories of Chernobyl. On my work shelf right now you’d find How Forests Think: Toward an Anthropology beyond the Human by Eduardo Kohn; Cecelia Vicuña’s Spit Temple; Donald Revell’s Invisible Green; Claudia Rankine’s Citizen; there’s The Dream of the Audience on the work of Teresa Hak Kyung Cha; Fortino Sámano: The Overflowing of the Poem; oral histories of Chernobyl; Levi-Strauss’ Tristes Tropiques.

Would you tell me a bit about yourself? Anything you are willing to share would give a reader more insight into your life and work?

I’d like to think of myself as disappearing into writing or visual work– but your questions ask me to see differently. I have a background in visual arts — and make my living as a designer in an architecture studio — visual poetry collaborative — with my husband, architect and painter, Thom Cowen. I spend time with things like details for copper flashing, concrete, window walls. I love the tangibility and the concentrated care of people making things. Our projects are mostly on the coast in Big Sur, so there’s a lot of contact with wild places.

As we talk, it occurs to me that I basically mess around with different things that don’t usually go together — like architecture and poems. Maybe this is another way to put metaphor into practice –bringing together the unlike through previously hidden connections.

Also, I would probably go crazy left to words alone. I need paint, twigs, sheet metal, drawing in order to speak.

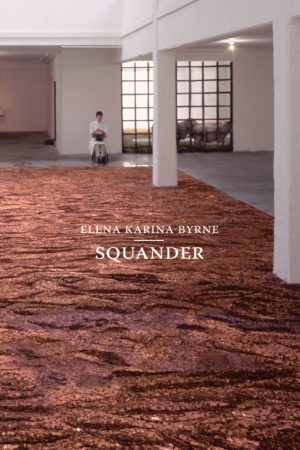

You were instrumental in the selection of the image that is used in the cover design for this book. Would you describe your considerations regarding the cover image? How does this cover align with your intentions for the book?

Since the animal of OUR ANIMAL cannot really be represented literally, I was looking for an image would be biotic, metamorphic — that would connect to the act of writing and the densities of the texts. I am so thrilled that we are able to use this incredible painting by Canan Tolon.

Working from her Emeryville studio, Tolon is a pre-eminent artist in Turkey and internationally known. Her work is mysterious, complex and gives itself over to forces of nature, time, rust, accident, ruin and repair. She engages subjects of displacement, borders, what Cecelia Vicuña calls — “the Precarious” — in entirely unprecedented ways.

Canan is also a long-time friend — we were house-mates in graduate student days in Berkeley, telling stories and reading aloud by the fire. So bringing our work together in this book is immeasurably wonderful for me. I’m so grateful for this process.

In Our Animal, poet and artist Meredith Stricker focuses on the person and writing of Franz Kafka. His themes—estrangement and Jewish exclusion—become her themes and prefigure her personal interest in the Shoah. Kafka, man and writer, is presented in a series of deeply researched “chapters.” . . . Thoughtful and moving, Our Animalserves the additional purpose of sending us back to Kafka, our antennae tuned to the distinctive frequencies of his pathos. As Stricker says, offering what may be an explanation for her deep engagement with him:“if words cannot transform me, what can [?]”

CHAPTER TWENTY: AMPHIBIAN

pay attention –

“I lay on the ground by the wall, writhing in pain, trying to burrow

into the damp earth”

a kind of castle or schloss looms and broods in the near-distance

guarded by sentries with rifles slung across thick uniforms

that resemble hair-pelts as they slouch in attitudes of sadistic ennui

ready for some sort of sport casting their casually indifferent

augenblick over the anguished new-comer