Description

Winner of the 2012 Omnidawn Open

Selected by Cole Swensen

Endi Bogue Hartigan’s Pool [5 choruses] takes the reader into a porous realm where singular and multiple voices fuse. In the context of high levels of public noise—reportage on the last decade of U.S. wars, elections, economics, more—the voices of these poems ask the reader to “separate out the chorus from the noise, separate us.” A journey into the accruals, interstices, separations and resistances of pooled and individual song, Hartigan’s poems explore the lyrical voice as a physical stream of sensual sound. How do we distinguish personal cry from choral cry, the “fragile, wet word of the spirit” from an over-lit or collective presence? Where does noise become its own form of silence? What is it to name perception—a local parade, a loved one, a singular shade of yellow—within a continually recalibrating multiplicity? This music moves through a complex intimacy–a world in which a woman’s reflection is never still, and a nation’s reflection is never still—and where the spectral, dizzying stage light holds a familial back yard and a choral shroud simultaneously.

Finalist, 2015 Oregon Book Awards Stafford/Hall Award for Poetry

Endi Hartigan’s Pool [5 choruses] reads as a celebration of the common etymology of text and textile, from the overall pattern of calls and responses that structures the entire book to the interwoven repetitions of arresting oneiric imagery at the level of the line. Phrase after phrase jumps out, clear, yet also surprising. Hartigan’s linguistic play is almost vertiginous, constantly on the brink of overbalancing—but she never does, instead landing electrifyingly spot-on every time, creating a gymnastics of the page that is simply exhilarating. And behind it all, always, is her music, making connections deep down at the level of conversant sound and echoed by the choruses that come in and out with their haunting intimations. Rich and yet fired by the pressure of restraint, this is a book that opens additional dimensions with every turn of the page.

Cole Swensen, author of Gravesend and judge of the 2012 Omnidawn Open

These gorgeous poems are exercises in presence apposed not to absence but to “slippage,” change, diminution, that humming, hymning poverty. In Hartigan’s bold lyric purview, the political is frankly flush with the lush landscape of phenomena: of lily and pine, of camellia, of roses and starlings, any of which might conceal an election or an economy or a war. Pool [5 choruses] emits a polyphonic incandescence that consumes itself by means of its own mordantly exquisite music. It is an extravagant assertion of lyric citizenship in an unstinting world.

G.C. Waldrep, author of Archicembalo

A book that performs as thoroughly as it proposes we step back, listen, think, and then step in, think, say, so that we’re invited to join in the making up of other choruses, one’s pool lends us to accompany our stories. This is a generous and generative book, it’s a thrill to be testing its waters, concerned with its singing collections of words.

Dara Wier, author of You Good Thing

Errata: Two typographical errors appear in the final printing of this book:

- p. 38: ‘tc. e’ should read ‘etc.’

- p. 77: ‘Goof morning young leaf‘ should read ‘Good morning young leaf‘

About the Author

Reviews

Excerpt

Endi Bogue Hartigan’s One Sun Storm won the 2008 Colorado Prize for Poetry, and her work has appeared in recent years in Chicago Review, Verse, Colorado Review, Pleiades, VOLT, Free Verse, Tinfish, LVNG, Quarterly West, Peep/Show, Yew, and other magazines, as well as the anthology Jack London is Dead (Tinfish Press, 2012). She lives in Portland, Oregon with her husband, poet Patrick Playter Hartigan, and their son, Jackson, and has lived most of her life in the Pacific Northwest and, as a child, in Hawaii. In the last few years, she has been a member of the collective of poets who organize the Spare Room reading series, and has engaged in a number of collaborative projects with Portland visual artists and writers, including the work of the 13 Hats artist writer collective, and a collaboration with artist Linda Hutchins which included a process-based exhibit and a chapbook which grew from it entitled out of the flowering ribs. Endi has worked for many years in communications for Oregon’s public university system. Her website is at EndiBogueHartigan.com.

A brief interview with Endi Bogue Hartigan

(conducted by Rusty Morrison)

Can you speak to the title and how it resonates through the poems in this collection?

“Pool” in the title acts as a verb, and I’m drawn to that sense of suspended liquid action. I think of these poems in movement. And I think of the collection as a whole as seeking not to answer but to enact certain movements: movements between the collective intimacies which form an individual and a choral collective, reflection and the unstill leaf-catching surface by which it’s perceived, the reports of our nation’s wars and actions and our implicit (and explicit) participation in those actions. There are 5 sections to the book, and while I refer to them in the title as 5 choruses, the number 5 is kind of the tip of the iceberg in numeration, and the act of identifying or acting out where voices begin and end was part of the allure in writing these poems. If I count them, the counting changes: sometimes I see the chorus as one chorus interwoven or spectrally diffused, sometimes innumerable, in some poems can’t be counted because they are fragmented and bent, sometimes absent. The word pool also picks up from one of the epigraphs which is an excerpt from the poem Balcón by Federico García Lorca, and there are several poems in the book which take off from this image of a girl, Lola, looking at her reflection in a pool. It’s a very simple image but the fact that she returns over and over, her singing of saetas and a sense of this local ritualistic action, the orientation or disorientation suggested in her returning to the pool, resonated for me.

I was delighted when Cole Swensen chose your book to win our open book contest. Your use of language is so exhilarating. There’s humor here, but never cynicism. Some of your reversals and repetitions are especially delighting and demanding. Can you speak to the formal variety in this book and how you envision the whole?

I was incredibly honored that Cole Swensen, whose work I very much admire, chose the manuscript. From the start, I felt this was an explorative project but not like formal research—it was more like the fascination of a blackout, exploring a dark room with your hands to find your way, except you suddenly don’t know what the room is, or what your hands are made of. I had never played with multiple voices, for one, but found myself in a place in which I felt that I needed to. Years ago I was enchanted with the chorus of classical literature—the scolding or commenting choruses of Sophocles, Euripides—but in this project the chorus came into my work through a slanted surprising challenge to myself. I felt that the sometimes official public sounds around me—the reported “voices” of wars and elections and terrorism and counterterrorism and economic woes—and the everyday more intimate touch-points were mixing, willfully or not. I started writing within that sense of public noise by listening for differentiations in sound and noise, and the listening was from both within and without. Things changed almost immediately. The choruses became multiple, the singularities became choruses, there were interstices and privacies and missiles and birds. When I entered this writing, I had to enter from a different stage every time in order to enter it, and this is where the formal variety came from.

I think I enjoy writing most when I am writing at the edge of my own knowing, where the explorations occur simultaneously and unexpectedly across liminal and linguistic and intuitive and emotional planes. I have been working with repetition for a while now as a way of moving. I don’t actually think of repetition as a thing in itself in the course of the poems, it’s like one organ among all the other interconnected organs of sounds and sense?which move together as one animal as if it is living. I like how repetition can move me through a series of orientations; it can calibrate and recalibrate a meaning or phrase subtly in different contexts. If it’s a human animal, maybe repetition is its gait.

In thinking about this text as a chorus, can you speak about which voices were the most difficult to hear and translate upon the page? Were there any voices that would not allow you to bring them to fruition? Which poems/pages do you recall as being the most vexing to complete? Were there any poems that surprised you, as you found your way through the formal process? Were some truly experiments? In what ways?

I like that you ask what I “hear and translate” on the page, because my process in writing this book was definitely a process of listening. One poem that surprised me in this regard was chorus inventing lilies in that the italicized choral voices emerged from listening. I started out writing lines surrounding what I sensed as an overlapping starkness of lilies and poverty and determination and devotion. I have never written fiction because, in part, I am terrible at writing dialogue, but this dialogue came in by surprise. With each of my entries in this poem, I found myself adding these short, parceled-out, elucidations and commands, and I realized it was a different voice. The chorus kind of talked back. Overall, I think one of the most challenging and surprising aspects of writing this book was that it was a kind of tug of conscience for me to enter from a new place formally with each poem, in order to necessarily do my hearing as well as what I didn’t hear justice. The choral gave me new ways in where voices emerge and differentiate and interstice and expand, but I didn’t want its force to be the force of a crowd. I had to find a way for language to be able to reference actual lives in the context of what is not referenced too, to mention things unspeakably embedded and complex in actual lives, with actual camellia bushes and layoffs and children and hopes and the 9/11 “anniversary,” which I didn’t want to merely report in stillness or claim an unfounded authority of report. I felt the danger of both over-speaking and under-speaking, and as a result the particular entrance point for lyric felt like a very tenuous easily slipping place; there is a series of poems necklaced throughout the book that explore this idea of “slippage,” which were especially challenging to write because I was writing at and from that point at the same time.

I think one reason the chorus allowed me to navigate here is that although the chorus is active, it is distinct from the actors. The chorus is there beside the actors while in the same viewer space. It is a more like the consciousness of a river flowing through a town and catching its garbage and its paper boats and sun. It lives in both a liminal spirit space and an actual stage space and fluctuates. It absorbs and acts out of absorbance, and speaks in a sort of molecular way to what we have absorbed. The poems that truly direct the reader in scores of two or more voices, such as Running sentences were definitely experiments for me and I had to rely on my own sense of hearing the voices and their sometimes very slight differentiations or locations on layered planes. One thing that helped me tremendously was reading these poems in public, and having friends help me read them at various performances, including a 2010 Portland Polyvocal Poetry Festival organized by Spare Room here in town.

Probably the most vexing element for me which took hard listening was the sequencing of the poems in the book, the overall architecture. I had to listen to them inter-web and talk amongst each other over time, and keep working with the book carefully, before seeing it ultimately crystallize in this sequence and these 5 sections. It took me a long time to figure out that the poems in yellow yellow yellow which I had written concurrently and had held separately on my desk were actually in conversation here. Adding that allowed me to think in terms of sections, which then fell into place.

Would you tell me a bit about yourself? Anything about you that is not in the bio printed in the book, and that might give insight into your more personal relationship to this text?

For my work, for the last ten years I have worked in a public policy environment in communications and project support for the Oregon University System, the administrative offices for the seven public universities in Oregon. So I have been exposed to, and in fact have written and edited much language of report, thick with data, category, numeration. As part of my work I also looked up news clips on the universities by searching the daily news of many papers every day, and in the process was exposed to a voluminous flow of media headlines and the kinds of news that makes headlines, often violent. I think that the sense of public noise and the questions of identification in this book were probably influenced by this exposure. I am interested in how the reports that we hear?and even those we tell of ourselves?play on or into our kind of liquid beings. At the same time, for several years I have been exploring Quakerism and its silent form of prayer; I don’t want to over-interpret this connection, it’s probably best left loosely near, but the possibilities of silence certainly interest me on numerous levels?I entered this manuscript with a sense of wanting to write with a consciousness of both noise and silence, a fairytale of reconstituting sound space around me.

I have lived all but two years of my adult life on the west coast, and my childhood primarily on the Big Island of Hawai’i. I think about how these landscapes play in on my obsessions. There are images of course: ginger blossoms and surfboards and sand. But beyond that, I look at these sometimes half-formed emerging, shifting, choruses, my drive to somehow expand their contextual stage, and I think of the landscapes that have informed me as places where expanse dominates, and where for better or worse, the strings of history and information are obvious in their incompletion and their frays. My landscape is also one of family?my husband Patrick and our son Jackson ?and my life as a family disallows me from negating the immediate, the daily, touchable and untouched world.

Who are the authors with whom you feel a kinship? Who are you reading currently?

I am currently reading Vanishing Point, selected poems of Valerio Magrelli (translated from Italian by Jamie McCendrick), whose strange metaphysical observances are really exciting. I’m also reading the almost chemically dense When I was a Child I read Books, essays on faith and science and writing and culture by Marilyn Robinson, as well as Hello, the Roses by Mei-mei Berssenbrugge, incredibly intricate and linguistically sensuous meditations, and before I go to bed lately I’ve been reading Willa Cather’s Oh Pioneers and melting into those fields. I have felt so many kinships over the years, many with authors who are strangers or dead, but I tend to see authors as so specific in their poetics that it feels intrusive in some ways to claim a kinship. In the last couple years, some whose work has been particularly exciting to me or has prompted my own conversations include Inger Christenson translated by Susanna Nied, Mei-mei Berssenbrugge, Dan Beachy-Quick, Anne Carson, Eleni Sikelianos, G.C. Waldrep, Amy Catanzano, John Taggart, Robert Fernandez, and Mary Szybist, with whom I’ve exchanged work in development, including this manuscript. I have been married to poet Patrick Playter Hartigan for 16 years and his formally innovative work and creative process speak continually to me. When I need to leave the contemporary I have lately gone back to the Greek classics, as well as to Lorca and Dickinson. I’ll add that I have also been a member of a collective of poets who organize a reading series, and while I know your question is pointed more at the page, I certainly feel kinship with the community of poets here in Portland with whom I collect every week or two to listen and learn.

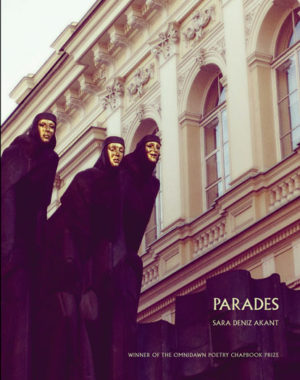

You chose the image that is used in the cover design for this book. Can you talk about your reasons for your choice?

I saw Betty Merken’s oil painting Ascent at Laura Russo Gallery here in Portland, and was immediately taken with it. It’s a captivating painting, with these nuanced and bottomless layers of color that are of course only entirely visible “in person” on its 60 by 68 inch canvas, but I’m happy that the cover image brought out much of that complexity. Merken is based in Seattle, and I didn’t know her personally, so I asked her out of the blue to consider a painting for my book and she was so kind to allow us to use this image and to trust my sense of connection with it. I think what I was most drawn to was the sense of the individuation and emergence of these spectral orange blocks out of the larger liquid, a numerated multitude within a greater liquid multitude, which spoke to me in the context of the book’s exploration of the individual within the collective chorus. Also, the suggestion of repetition of these orange shapes with their shimmering reflections brought up interesting echoes of the poems’ uses of repetition and Lola’s reflections in the pool. It’s a lush and uncanny image.

As Hartigan’s muscular poems wrestle with interchangeability, so too do their innovative structures challenge its boundaries. Acrobatic and playful, the poems turn back and reflect on themselves, daring readers to consider intention and arbitrariness at once. And yet, the book is wary of the total annihilation of individual meaning: “The slippage that we must avoid is a certain blanketing in which/ the delicacy of perception is lost.” Hartigan’s poems take simultaneity and expose it: “The news is on, the news is on at the same time as the game, sorry, it’s on at the same time, I’m sorry.” Individual moments are individual for having been chosen—lifted out of the noise—and Hartigan’s poems make the claim that the act of choosing, no matter how choral the result, is of the greatest importance.

… the “slippage” of Hartigan’s text makes for a slow and beautiful dismantling, as if a flower that dies and slowly drops off its petals. It moves like a dance, where the immediate proposals for beauty are the only aspect that matters. Hartigan’s book is an actual story—but an obdurate reader may miss it because the narrative is fragmental, and drifts like movements which possess their own immediate merits. The symphonic quality is evident. Stravinsky’s “Rite of Spring” is not a piece which moves in a deft pattern, and neither is Hartigan’s collection.

The five sections that make up her Pool [5 choruses]—“gallop,” “lily tally,” “Lola, backstage,” “yellow yellow yellow” and “office of water”—are built of poems that extend and pull apart the line, composing lengthy linear stretches in the smallest of spaces, writing poems both choral as in the multiple/polyvocal, and in the elegantly lyric. As she writes in the poem “Flurry series,” subtitled “4 choruses”: “The tree transferred choruses / from eaves to branches—from branches to eaves— / in their slippers and gowns, in their suits and linings and cowboy boot / dresses, in prints and in tresses and costumed sounds—[.]” What appeals most about these poems is how much manages to happen in such a small sequence of moments, moving one to the next to the next, each one sending ripples that continue for miles. Where Hartigan shines is in the lyric disjunction, composing poems that work to explore the seriousness of real events and the weight of how the world sometimes happens to be, all while managing a lightness of line and a spark of phrasing that bounces.

We cannot help ourselves

but believe. Look what people do.

We cannot help ourselves to

believe. Look what people do

and believe. I can’t believe it

said the plum trees shivering

and then the blossoms showed

up scattered, sideblown,

not just down. We cannot help

ourselves to everything

said the people unbelieving,

shaking heads. How can we believe now, look?

Atrocities blossom also, look.

The trees said help yourselves

to blossoms: democratic trees,

dreaming lessons. We believe

in teaching belief said the trees.

We cannot help ourselves with

blossoms, to blossoms of belief.

White blossoms fell on our hair

a weight barely there, so we

left them till they blew.

![Pool [5 choruses]<br></br>Endi Bogue Hartigan](https://www.omnidawn.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/01/Pool-Front-Cover-WEB-200x300dpi-RGB.jpg)