Description

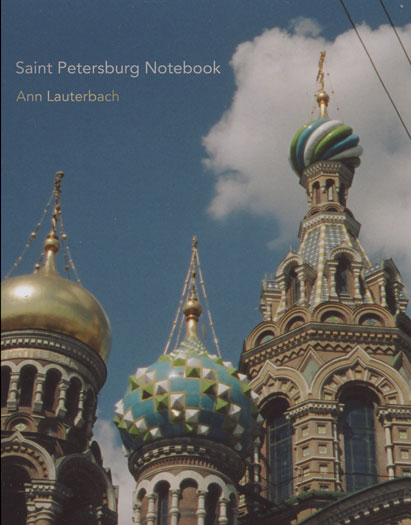

Saint Petersburg Notebook was written in the summer of 2006, when Lauterbach joined the Summer Literary Seminars and found herself among a lively contingent of writers dropped into the layered world of the great Russian city. The Notebook gives us glimpses into her experience of cultural difference, in which the sense of self is measured against a proliferating ensemble of art, poetry, urban beauty and terror in the land of white nights.

The notebook as a literary form is peculiarly inscribed in the Russian tradition, especially in the literature of Petersburg (Gogol’s Diary of a Madman, Dostoevsky’s Underground Man, Daniil Kharms’s Blue Notebook, and the “blockade notebooks” of World War II). Ann Lauterbach’s St. Petersburg Notebook partakes of this lineage, as it investigates both the psychic landscape and character of the post-soviet human and the traveling writer’s own estrangement from self and time during the white nights. Benjamin’s Moscow Diary hovers, closer perhaps than the visits of English-language poets across time and aesthetics (Marvell, Frost, Hejinian et al). Her observations of Russians’ muteness or lack of expressivity, the hollowness of their cultural spine, and their desire to be superficially European, strangely echo the Marquis de Custine’s 19th Century critical travelogue. The porous space of Petersburg, cast in oblique light, is palpable as an unsettling dream in this brief, haunted notebook.

Matvei Yankelevich, translator of Today I Wrote Nothing: The Selected Writings of Daniil Kharms

About the Author

Excerpt

Ann Lauterbach, poet and essayist, is the author of nine books of poetry, a collection of essays, and numerous works on and with visual artists. She is co-Chair of Writing in the Milton Avery Graduate School of the Arts and Schwab Professor of Languages and Literature at Bard College. She lives in Germantown, New York.

1. Meanwhile

I’ve been listening to Pandora radio, set to the Bob Dylan station, now playing Jimi Hendrix singing “Like a Rolling Stone.” The sound seems distorted on all the songs, as if filtered so many times it has lost some sonic ingredient, whatever it is that makes music specific to memory’s aural imprint. I have huge old Yamaha speakers, so perhaps it’s that the digital radio doesn’t want to be exposed to speakers that were created for analog sound.

Before I was listening to Pandora, I was reading Herta Mu?ller’s 2009 novel The Hunger Angel, sent to me by a young German friend, along with Mu?ller’s Nobel Prize acceptance speech. Both of these writings are acutely spare, like sharp needles that pierce to the core and leave tiny soul scars. In the case of the novel, the core is depredations of exile; specifically, exile from Romania

in 1945 to work in the Russian labor camps. The book is narrated by its protagonist Leo Auberg and Leo is based on the life of Oskar Pastior, the Romanian-born German-speaking poet (and member of Oulipo; translated by Harry Mathews, published by Burning Deck). Herta Mu?ller had spent many hours in conversation with Pastior; they had intended to publish a collaboration, but he died, in 2006, before this could happen. Instead, she wrote The Hunger Angel.

Mu?ller’s novel has made me think about the relation between actual experience and memory, and memory and the imagination; about the relation between duration and endurance within physical and mental realms of life; about the complex arena of translation in its

broadest sense. I have thought of these things often over many years, so I am returning to them.

There is a passage in The Hunger Angel about shoveling coal with a heart-shaped shovel. It’s an account of physical movement, set against or into a near absolute void, caused by the body’s hunger and the spirit’s depletion. In her Nobel speech, Mu?ller speaks about the sound of language in relation to material objects and to emotional gesture. She writes, “The sound of the words knows that it has no choice but to beguile, because objects deceive with their materials, and feelings mislead with their gestures. The sound of the words, along with the truth this sound invents, resides at the interface, where the deceit of the materials and that of the gestures come together. In writing, it is not a matter of trusting, but rather the honesty of the deceit.”

These delicate coordinates captured, as Mu?ller says, by the poetics of sound, animate our awareness of what it means to elucidate the historical real as imagined presence.