Description

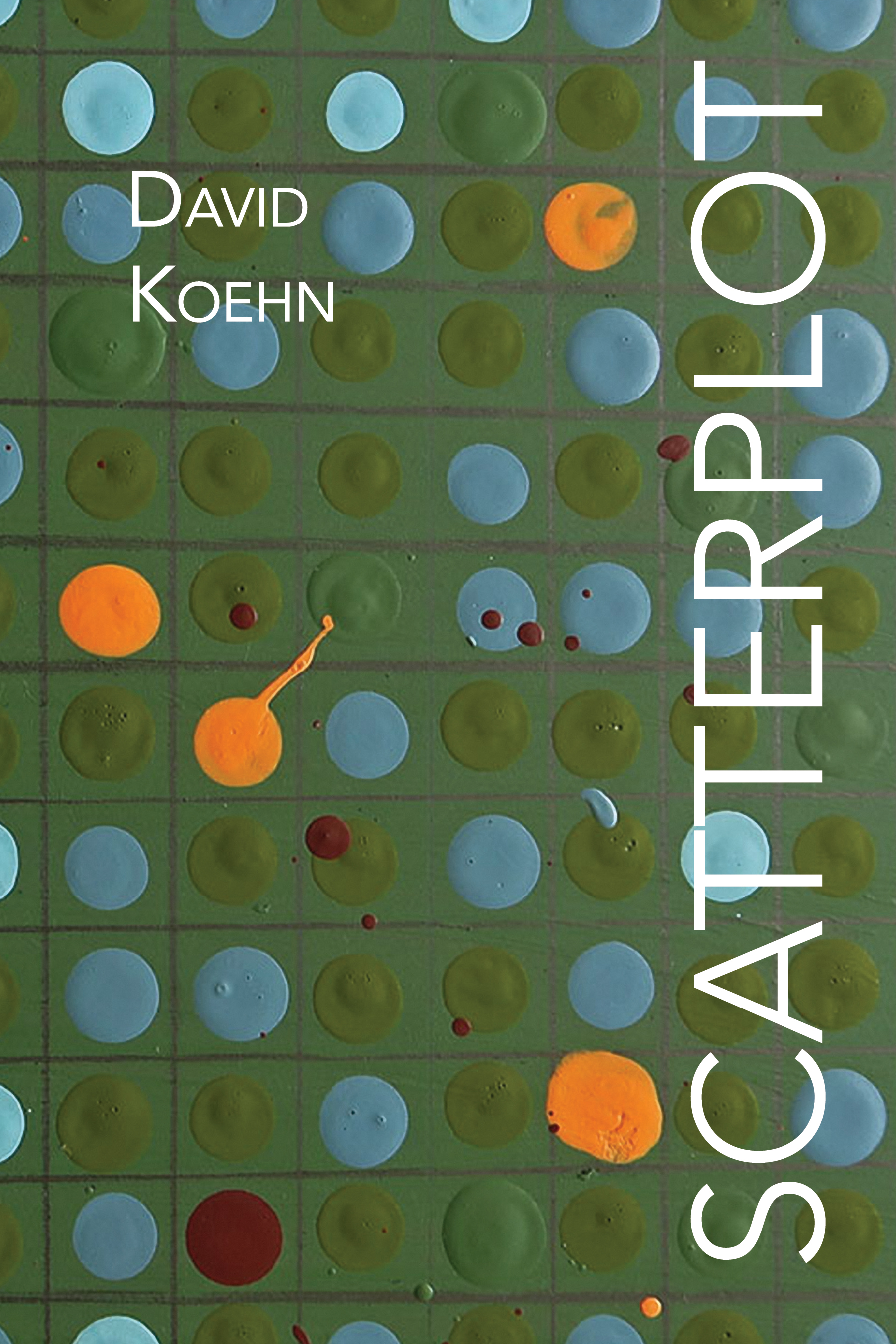

Scatterplot navigates a vast landscape of imagination through variations on being lost and found. David Koehn’s investigative journeys allow space for the failures of consciousness and gaps in the knowable as he traverses a sensory terrain through the shadow of natural history and the glow of the family room TV. In this wilderness is a father and son walking the sloughs of the California delta, searching through the mayhem of a world dismissive of, but also requiring, love.

Koehn diagrams connections from media, art, film, music, nature, history, and his own family into a web of coordinates that form constellations of beauty and tragedy. He moves from the music of the Bad Brains, to the grotesque lifecycle of the Tongue-Eating Louse, to the deconstruction of Mutant Mania toys, and on through the poems of David Antin and the suicide of Anthony Bourdain, building a fantastical world from the wild realities of the real one. In a universe so full of imperfection one can’t help but both laugh and cry, the poet embraces the present while taking responsibility for his own insufficiencies. Amounting to a mix of experiments—erasures, surreal narratives, collage, walking poems, and more—the delta between right now and forever feels both inescapably present and delightfully confused. Immense vulnerability, infinitely odd observations, and uninhibited daring populate the psychological terrain in the poems of Scatterplot as Koehn invites us to join his spiraling poetic exploration.

From its first line this book announces itself in sinuous rhythms of sound. Koehn’s sound is contemporary but his tricks ring with ancient echo–apophatic exuberance resonates against aniconic description and coy anacoenotic inquiry. Still, it’s no dusty fairy tale, nor rangy arrangement–it’s here and now, immediate and incisive.

Kazim Ali, author of Inquisition

David Koehn’s playful new book of poems, Scatterplot, intertwines the personal and the political, the past and the present. When Koehn writes, “I am what happens before the artist covers the canvas in paint,” he means it. His intimate, fine-grained attention to vivid details, as well as his energized lyrical juxtapositions, are restless yet fluid, which is to say, they are a pleasure to read.

Sholeh Wolpé, author of Keeping Time with Blue Hyacinths

David Koehn’s Scatterplot is a book full of names and near-misses best described by its attention to narrative…when it is the narrative we associate with dreams! Or as Koehn himself says, “I was stumbling around the aisles of a dream.” This line in particular has everything to do with what I love most about this book. Every poem throws itself headlong into litanies of images reminding us that, even when we are lost or dying or anxious, we are still very much alive.

Jericho Brown, author of The Tradition

Good poems always know more than their poets, and David Koehn’s poems in Scatterplot are very, very good—as the book progresses, they illuminate their expansive knowing in increasingly fabulous ways. One poem names its four target readers—Bay, Rusty, Scott—and then lists us, the reader, as its fourth. A poem erases itself as we read, another implores us to cut its pages into confetti. A long poem asks, “Can every line carry the whole tune?” and then proceeds to investigate. It’s a wild ride. Koehn has made something irreducible here, electrifyingly new.

Kaveh Akbar, author of Calling a Wolf a Wolf

Named for the visual depiction of statistical data, the contemplative second book from Koehn explores domestic chaos through a sequence of long poems…Alaska and San Francisco serve as settings for zoological trivia, and the lives of grown-ups often seem beside the point, their failures devolving into bad data…Some poems are collage-like in nature while others tell surreal tales and rely on word games…Humor and verbal play appear to offer a coping strategy for the vulnerability and difficulties of daily life, which Koehn sensitively renders in this observant work.

Scatterplot is a book that thrives in the world of a pandemic or of the internet…Koehn understands the need to recognize the shape of the collective just as well as the individual. By recognizing the gaps between moments and recognizing the shape and substance of the space between them, we arrive at a fuller idea. The self-awareness of the poems and the we-awareness of the book helps make sense of the world at a time when the space between seems to dominate.

Von Wise, Gulf Stream Magazine

Reviews

About the Author

Interview

David Koehn is the author of several books of poetry, including Coil and Twine. He lives in Discovery Bay, California.

An interview with David Koehn

(conducted by rob mclennan for rob mclennan’s blog)

1 – How did your first book or chapbook change your life? How does your most recent work compare to your previous? How does it feel different?

When Twine, my first book won the May Sarton Prize from Bauhan Publishing (May Sarton New Hampshire Poetry Prize) — literally nothing around me changed. Kids were still the kids, the job was still the job, the work was still the work. No one came knocking begging me to publish in their magazines. No accolades beyond a sticker on the book.

I found in publishing the first book a kind of peace in knowing that the work before and during the making of the book — apart from the grunt work of revising for publication — was the same as before: pointless, fruitless, a waste of time, a nothingness, and therefore a joy. I was relieved by the win because I could stop being another poet chasing their first book publication. I could stop trying to be a poet trying to win a book prize.

It was gratifying to know how little the outcome mattered. And that, therefore, all that mattered was the joy in doing the work. And reading the work of others. My lifelong collaborator, Rebecca Resinskl, once said, she was “highly suspect of laurels” — and the closer I come to the worlds of the anointed the more deeply I love her expression.

In Scatterplot I explored the limitations of what I was taught the poem could accomplish. Given forms, nonce forms, forms from Western Tradition, Forms from the Eastern tradition, short line free verse, syllabic poems, metric verse — and while, as William Logan declared to me once that I have a deviant imagination, I found that what I’d been taught, the constraints of the lessons I’d learned, limited the kinds of aesthetic experiences I could deliver.

So, somewhat systematically, I decided to break all the rules I’d given myself for writing poems. As I wrote, and felt my head bumping up against something, I would embrace and convert that sense of boundary or transgression into the work of that piece — meaning I attempted to write successful poems breaking all the rules I believed I could not break. The tailored clothing of Twine did not fit the adventures I wanted to take in my work in Scatterplot. Plus, the suicides in the midst of our friends and family broke something in me — like I couldn’t afford to worry about poetry, I could only afford to see and say.

The number of voices in my head and the number of voices in my work did not match. I think about Harryette Mullen and Lenny Bruce. I think about Dag Hammarskjold and I think about Li Bai. I think about C.D. Wright and I think about Larry Levis. I once told C.D. I work on poems for years, sometimes decades, before I think they are ready. She thought that “a little much.”

I listen to Velvet Underground and Bad Brains and Miley Cyrus on the same playlist. The struggle to navigate my love for the elliptical in the same breath as narrative competed with my desire to write imagistic short line free verse which correspondingly vexed my deeply rooted desire for given meters and forms. Every poem to me is a sonnet and if not not a sonnet than a double sonnet and if not a double sonnet — a triple sonnet — etc…

I continue to believe poets write poems to the generalized shape of where they imagine the poems will appear in print. I want to write away from the idea of a page or computer screen or phone screen as the frame for the poem. And so over the last few years, for Scatterplot, I have been writing these otherworldly walking and talking long poems based largely on walks I take with my son Bay.

Into nature per Muir, “for going out, I found, was really going in.” Letting things stray, encouraging chance (a la Cage) in their construction, making all voices and movements allowable (a la Antin), and so these recent poems have journeyed to new places, usually without me. And at other times I found myself looking at a place over and over again — hiking the same 3-mile loop every day for a month. How could I lean into what Arthur Sze asked: “Is it possible to write a long poem where every line is a poem?”

My most recent work, therefore, is a reflection of writing in a space free of all the rules I once gave myself. Of walking and talking and sensing. I experiment with new constraints that flew in face of my old assumptions. I could break the bowl in different ways. While in my first book I rolled through forms and meters and imitative free verse rhythms, in my latest work I absorbed all such and have found new ways to make it anew. Scatterplot contains, what I think is, the best work of my life.

2 – How did you come to poetry first, as opposed to, say, fiction or nonfiction?

Music. I noticed the way things sung made me feel. Prose did not and could not make the hair on the back of my neck stand up. Prose didn’t catch the reaches of my consciousness. What made me alive with attention? Poetry. Rock-n-roll. Punk Rock. Jim Morrison. David Bowie. Bob Dylan. The Replacements. The Sex Pistols. Robert Johnson. And by way of Bob Dylan, Dylan Thomas. And by way of Bowie’s Cracked Actor, Shakespeare. So somewhere in the drift between Dylan Thomas and Shakespeare’s Sonnets, between Richard Hell and the Voidoids and Millay’s sonnets (a gift from Mother) — via these people in high school I stumbled into the art.

3 – How long does it take to start any particular writing project? Does your writing initially come quickly, or is it a slow process? Do first drafts appear looking close to their final shape, or does your work come out of copious notes?

I am always writing — listening for words or a phrase that catch my ear. If I hear something I like, I’ll jot it down. I collect these scraps of sound over a long period of time. But I am bursty. When the right conjunction of time and energy and focus collide I enter a manic phase and generate a tremendous amount of stuff in a very short time. I slide into this phase unapologetically and freely and embrace it.

I know the spike will end — I will enter a dormant phase where I’ll wish I was producing but am not — likely just collecting. Collecting snippets and phrases again waiting for the slide downhill. I ski freely and wildly downhill — knowing I might get hurt or fall but I will enjoy the ride. I also know every hill has a base, and I’ll slide back into the lift line and ride the lift back up to the top. I’ll shiver but I’ll be reflecting on the last run and looking out over the mountain for my next line…

Scatterplot looks across lines and plots of land. Collects unstructured elements and characteristics and maps them into patterns. In Scatterplot — the pattern in the scatter reveals the plot. Changes or “delta” in the angles of perception and sensation in Scatterplot drug the work with unforgivable allowances.

The meandering “delta” poems serve as the map graphs of book’s explorations. I started the “delta” poems as a result of taking long afternoon walks along the local riverways of the Califinia delta with my youngest son, Bay. At the time, he was 8 years old, currently 10, and who knows what age when this sentence will be read by you the reader.

During our walks, he would surface observations about his day, the plant life we walked through, the animals around us, and other imaginings. His observations would slide into and out of my own consciousness which sometimes would build on what he was seeing and sometimes were riffs that spliced into my own thoughts. The work contains his expressed imaginative world as part of their through-line…

In particular, I found these poems exploring the failing relationship I have with his mother — and our family life. From there I started writing “conventionally” — read: “the way I was trained to write” — but these ways of writing did not give me access to the depth of imagery, language, and textures of consciousness I found emerging. So because “autobiography” and “confessional” and “memoir” hold a place of ill-repute in my mind, I felt these poems pushing me beyond my comfort level.

In these free-verse poems, I break all my own rules of shape, form, and content. I have no idea if readers have any interest in the micro details of day-to-day failings and mistakes and misperceptions and character flaws — but I do. I fatigue of my own rebel nature that wants to pit the belief of my rightness against the world. So I found myself writing into a kind of capitulation and ownership of the disaster — an acceptance of my responsibility for the destruction of the world — acknowledging my feelings of helplessness and lostness and somehow in all that detrital material stinking up the substrate — I hope.

In ecosystems, decay is a sloppy, stinking thing — but the source of what’s next. I look for the glittering phytoplankton shimmering under the moon in the sulfurous wretch of a diseased slough at ebb tide. Sometimes I find it — sometimes I don’t. I struggled but ended up iterating my way into writing in a style of largely “long line free verse” interspersed with other non-linear verse types — an erasure or two — and a poem I suggest you cut up into confetti.

These approaches let the poems have space and time and duration and moved them beyond the bumper sticker compression of imagery I had used in prior work. In this process, to quote Cage, I “let the outside in” in ways I had never allowed or permitted or even considered. So as my faculties woke up to where these poems have taken me, these poems push themselves onto the page and keep leaping forward from where they started…delta after delta.

4 – Where does a poem usually begin for you? Are you an author of short pieces that end up combining into a larger project, or are you working on a “book” from the very beginning?

I started just writing poems. And publishing them. Not many at first. Then many. Then too many. And I had no concept of assembling them into a full-length book. I had won a chapbook contest but that was largely a reflection of having published some poems from my MFA Thesis, stapling them into a collection, and submitting the ream to a few random places. Organized more by the force of the MFA energies in my thesis than authorly concerns.

A few years back, I attended the Napa Valley Writers Conference where I had the good fortune to work with Arthur Sze (Sze remains an influence on me). I also had the good fortune to meet and chat with Forrest Gander who — in short — suggested I stop publishing poems. He suggested I focus exclusively on assembling a book. So the first book was a retrospective process based on a prompt from Forrest.

The second book started out as a retrospective process and as I shaped the content became more project-like. Rusty Morrison, the managing editor at Omnidawn, noticed the delta poems creating propulsive energy — and I didn’t seem to be done writing them — even though she had accepted the manuscript with only a handful of them in the original. Much to her delight (or perhaps dismay) the delta poems displaced other work and became the score for the work in Scatterplot.

5 – Are public readings part of or counter to your creative process? Are you the sort of writer who enjoys doing readings?

I love reading! I love doing/giving readings! But they take time, and effort, and logistics, and like I said the paparazzi is not beating down my door. So, in general, I read with a few friends now and then here and there. The last few have been with Omnidawn folks at AWP, and Omnidawn folks at Poets House in NYC, and with Bob Hass at City Lights and with Bob at Studio One. I’m always game and I enjoy them. Do they figure into my process? Not really…

6 – Do you have any theoretical concerns behind your writing? What kinds of questions are you trying to answer with your work? What do you even think the current questions are?

What is the line Justice quotes from Cage? I always read it when I am reading from Compendium by Donald Justice, “Our poetry now is the realization that we possess nothing. Anything, therefore, is a delight.”

For me the questions are all related to accountability and reframing of assumptions. What we see is never just what we see. Our tastes, our preferences, are programmatic holograms. The variety and plurality of the world are like the quantum layer. And our perception of its connectedness and relatedness reflect the smoothness of the physics of time and space. In my small way I wrestle with artifice.

In Scatterplot, by way of example, I faced the challenge of resisting memoir — essentially moving from despising the use of memoir-like detail in my work to embracing such details and deepening the way such detail might braid into a poem. My ex-lovers, and my friends, and my life partner, they show up here — so I have to embrace that and they have to know they appear in the work. The music playing in a room, the tv show on tv, the painting in a wall, what I see out a window during a revision, children’s toys — the writing moment makes its way into the work — when perhaps at first my surround has nothing to do with the Axolotl the poem seems concerned with.

I faced the challenge of working in an entirely counter-culture mindset — the length of these poems, for the most part, do not abide the bite-size needs of Instagram and Twitter (both of which I use and love).

I asked, what does it mean to write a poem to the end of what I think the poem wants of me — and then push it further? And then what happens when I’ve reached the end of the second push beyond the frame I allowed it? And then do enact that again and again and again?

Julie Carr introduced me to this idea of revising the first draft forward — not back — not ending the hike at the first milestone but pushing to the 2nd or 4th or 9th or? But when I took the governor off I found myself lost, without a guide and turned to Levis and Whitman and Guest for guidance.

Keep in mind for Scatterplot I revised the majority of the Delta poems after publication — reducing their length on average by about ½ . This exposes the other challenge — of who in their right mind would publish such work? These rangy and unwieldy unsettled lyrics certainly confounded many editors. “I don’t get it.” and “Remember less is more — can you cut this to 1/3rd the length” and “Much to admire here but in the end WTF?” And so on… And I kind of agreed. I found them unlikeable, unloveable, unreadable, and unpublishable. I have some evidence after writing 30 or so and publishing all 30 that the last “unpublishable” proved false.

I faced the challenge of modifying my thinking of what kind of words and images would be acceptable in a poem. So I found myself reading O’Hara. The images in my world are scenes from the TV, from the backyard, out the window of a car at 80 miles an hour, from the window of a skyscraper, a plane. The imagery of my world is cluttered storage spaces and houses built in subdivisions and invasive plant species and migratory birds.

The images of my world are bad haircuts and algorithms and great blue herons. The images of my world are the stream of memes I receive on social media, the texts I receive while driving, and always some playlist on Spotify playing a rack of music I love. So how do I make room for these images and the words that name them? And so Ashberry, Ashberry, Ashberry…

So I faced the challenge of including so many referents in a world powered by the Web and by Google. In the age of Google the idea all referents live in the poem in of itself seems misguided. So I leaned into music, and art, and film.

Here is a list of all the songs in Scatterplot.

Here is the Spotify playlist of all the songs in Scatterplot.

Here is a list of all the media and films in Scatterplot.

Here is a list of all the books noted in Scatterplot.

I faced the challenge of having to accept that I have given all of my imaginative force to Scatterplot — untethered and without much rudder I record my float trips in the currents of mind and place — of relationships and culpability of fatherhood and friendship and all in the background of a natural world touched wholly by man — nature not untouched but rather manhandled.

In only a few snippets of time does the veiled world, nature in itself, peek through. And that is my experience of it — so I faced the challenge of having to acknowledge I am not good enough, I am not up to the task. I do not write with enough skill. My observations are not precise enough. My language and my syntax lack the elegance to make visible the contours of the experience I wish the reader might come in contact with. I do not possess the skill or range of heart or consciousness of dexterity of composition to meet the work and carry it as far as I wanted to. I tried and I failed.

I tried and failed again. I can say I am here — it is me — I am exposed on the shoals like a big husk of mussels at low tide ready to be pried open. A many-meat Prometheus — lol. The failings abundant and the shortcomings so visible — to lack the skill to make all this work matter is heartbreaking. But would I have it any other way?

7 – What do you see the current role of the writer being in larger culture? Does s/he even have one? What do you think the role of the writer should be?

I think writers as writers who don’t live face challenges poets who live first and write last don’t. The lens of the faculty poets can only be so wide — because their lenses all start from the same promontory. It’s a good promontory. Just not the only lookout that might work as an observation point. I’m always heartened when I see artists doing serious and excellent work who work day to day as nurses, doctors, boat captains, branches, ad salesman, programmers, insurance salesman — or otherwise. I ran the Grammarly word choice uniqueness algorithm over the last issue of Poetry…the data was kind of shocking.

8 – Do you find the process of working with an outside editor difficult or essential (or both)?

I love the experience of collaborating with others. I have never had a strictly editorial relationship though. When I’ve worked — even with editors — it has always been an aesthetic as well as textual interaction.

9 – What is the best piece of advice you’ve heard (not necessarily given to you directly)?

Take the cotton out of your ears and put it on your mouth.

10 – How easy has it been for you to move between genres (poetry to critical prose)? What do you see as the appeal?

I get discouraged from writing critical essays easily. With the “art” — when writing a poem I am experiencing a kind of process fulfillment — I am experiencing pleasure — and I would do the work of making a poem whether a poem comes out of it or not. Whether a poem gets made is not really the force behind the effort. If a poem gets made and never gets published — the joy of making happens nonetheless. McA Miller, an early professor of mine, likened it to Onanism.

Critical writing is an intellectual effort — in particular I deeply enjoy closely reading poems for their intricacies and textures and sounds and syntax and diction and rhythms and themes and all the stuff that Cole Swenson calls “literary noise” designed to keep our imaginations open and engaged. And yes, this kind of close reading I will do and enjoy and get great pleasure from when I am reading any poem. My participants in the Omnidawn Prosody and Revision workshop over the last decade can attest that the luxuriating I do in the deeper chambers of the critical works/reviews I’ve published on Seamus Heaney or Arthur Sze or Harryette Mullen or Gillian Conoley or Galway Kinnell or Donald Justice is the same luxuriating I do every time I read work. But the labor of translating all the fiddling and tunings and pluckings and sensings and finger tappings and tastings and imaginings and supposing into linear prose feels expensive and labor-intensive and — this kind of close reading — folks don’t really publish much of anymore. So over time I have shied away from it.

11 – What kind of writing routine do you tend to keep, or do you even have one? How does a typical day (for you) begin?

See prior notes?

12 – When your writing gets stalled, where do you turn or return for (for lack of a better word) inspiration?

I was once stalled for eight years. That pause made me accept patience and pause as part of my process.

13 – What fragrance reminds you of home?

In an iron skillet, filets of perch frying in butter

14 – David W. McFadden once said that books come from books, but are there any other forms that influence your work, whether nature, music, science or visual art?

Tucker Nichols :: @tuckernichols —

Long time fan of Tucker. The cover of Scatterplot is a painting of Tucker’s. A Bay Area icon really. What does it mean to see something simply in all its complexity — neither leaving out the layers of its being and yet surfacing the thing as its essential self? Tucker does this for me in his work. Tucker read Scatterplot and rendered a handful (almost a dozen) of paintings in response. I hope to acquire more of these or show them all at the readings for others to acquire.

Jim Christensen :: @youroldpaljim —

Lifelong fan. When I was a kid Jim made me brass thumb rub — it hung on a necklace around my neck for years — somewhere along the line the end of a relationship ended up with the necklace leaving with it. The underpart of the brass was curved like a small pill bottle so it nested in my pointer finger perfectly. The surface of it was flat across from one side of the perimeter to the other with a slight impression that nested my thumb — the fit was perfect and I would reduce my worry about anything in the world by rubbing my thumb on the surface of that copper. I miss it.

Truong Tran :: gnourtnart.com

Working in pieces of pieces of pieces with a calling to the public and social and political context of the Bay area — I fell in love with the patterns within the patterns of Truong’s work. Overtly social without being didactic. Visually stimulating patterns within patterns where the accumulation of the small amounts to a larger overall composition.

Nathaniel Russell :: @nathanielrussell

The social components of Nathaniel’s work are worldwide and Web-wide. “Resist Fear Assist Love” — Google it and the search will reveal what you need you to know about his social practice. I feel kindred to Russell because he draws a bird, a flower, a hand, a body, and can’t help but render himself into the feel of the image. He’s like a musician who when you hear them play a single strum of a guitar you know exactly who that player of the guitar is. Somehow they have tuned the guitar, and the pressure of their playing, the choice of the lick, the firmness of the fingering –one strum and you know. He’s a musician too. Hope he plays at one of my readings someday.

Scott Brennan :: @scottbrennan6

A poet and visual artist. Saved my life a few times along the way. Designed the now faded tattoo on my back — faded now. In a few days in New Orleans back in 1991 we both got tattoos and remain close friends to this day. My ideal reader. The one I hope to delight, disappoint and sometimes confuse. For many years he did graphical work and switched to photography where he focuses on the urban landscape — of Miami in particular. The way he sees the world reflects how rare we see things as they are. Not in motion, No people. How do things compose your view when seeing stillness and subtle presence?

Jon Fischer :: @feather2pixels

Handmade vinyl albums that play sound and music and he uses the rotation of the albums to render drawings. Directly connecting the patterns and sound so coming off the handmade vinyl records to the canvas or paper. This direct link between music playing off a record to an image visual on a surface appeals to me and feels like a metaphor for the way my consciousness aspired to operate when writing much of Scatterplot.

Irman Arcibal :: @indetirmanit

Irman developed a long series of “Eavesdrawings” where he would situate himself in an X/Y grid-like area. On his parent’s porch. On a college campus. At a park. And he would listen to the voices he heard. He would write down the words he heard in the X/Y space where he heard the voice/words coming from. Locating himself at the center of the page — he would write words from behind, in front, left, right etc… filling the drawing the word he heard by eavesdropping. Irman uses many chance operations and arbitrary processes in his work. This scattered input that adds up to a shape and experiences that delights the viewer delights me.

Hunter Franks :: @studiohunterfranks

I like Hunter’s social practice focused on engaging with people and place where his but is seated. There is a non-event and non-sensationalism to the form of surprise in his work. The everyday in itself appears rendered in value as is. The as-is world holds hope.

John Riegert :: https://johnriegert.tumblr.com/

John was a friend. John committed suicide. John was as creative of a human as ever lived. https://www.post-gazette.com/news/obituaries/2018/11/27/JOHN-RIEGERT-obituary-pittsburgh-artist-documentary-the-john-show/stories/201811270139. Drew a picture a day for years and years. My favorite is his odd, overly simple, comic rendering of a translation of Catullus’ Odi et Amo.

Daleast :: @daleast

The shift of perspective to the scale of Daleast’s building high murals — feels grand and impossible. He uses streamed banners of ribbons of line to paint large forms — often animals like Rams, Cheetahs, Ravens, Deer and so forth. There is no firm line or edge to the shape drawn in the mural — rather a kind of a gestural set of strands that constitute the contour. Social in charter and jaw-dropping in scale and detail.

Anna Secor :: @ChaosmosDichotomizers

Anna is a geographer. Anna J Secor, Durham University, Geography Department, Faculty Member. Studies Modern Turkey, Geography, and Gender. “…dichotomizers are discursive-material apparatuses for the production of Western epistemology and ontology. These fine machines perform a Bohrian cut that produces dichotomous paths for the categorization of otherwise ambiguous phenomena. We guarantee that these dichotomizers will provide the clarity, order, efficiency, and brutality that are so important for modern life.” One of the Anna’s my oldest daughter is named after. A woman in my youth who invited me in — I declined — a regret. Takes pictures of herself dreaming.

Rebecca Resinski ::

A personality throughout Scatterplot. My ideal reader. A godlike creature whom I can’t stand displeasing — a catalyst for all things — the skink in the flint. Produces concrete poetry artifacts under the Cuckoo Grey imprint. Collaborator. Met in high school, together for only a day or two in the past 30+ years.

Concrete Poetry Artist’s Book by Rebecca Resinski (Conway, Arkansas, USA)

&

https://queenmobs.com/2019/06/misfit-doc-5-quartets/

Ashwini Bhat ::

Ash and I met through a mutual friend and I found in her work the presence of the senses. Much of her work is sculptural — and the gestures, to me, represent a kind of connection to sound and sensation in addition to being visually 3-dimensional objects to look at and admire. They emerge — and some of the sensation I experience during the creation process feels visible in her forms. Her work questions the division between a final artifact and the gestures of its manifestation. I like that question. Alot.

15 – What other writers or writings are important for your work, or simply your life outside of your work?

Too many to name, and I name and have named them in my critical writings and publications, and by inviting them to be guests over the years in my workshops, so for the purpose of this interview I’ll keep the list limited to one: Rusty Morrison.

16 – What would you like to do that you haven’t yet done?

So many things. I’m a list maker and I have lists of various types that include dozens of things I’d like to do that I haven’t done yet.

To fit our working thesis in this interview lets stick with, publish a collection of my critical prose and various essays.

17 – If you could pick any other occupation to attempt, what would it be? Or, alternately, what do you think you would have ended up doing had you not been a writer?

I’ve never been a writer. It’s the one job I’ve never had. I’ve been a teacher, a house painter, a short-order cook, a data analyst at the EPA, a librarian, technical writer, a bartender, a construction worker, a stock boy, a tour guide, a product manager, a newspaper delivery boy, a deckhand, a tilt-a-whirl ride operator, a tech exec, an angel investor, but never a writer.

18 – What made you write, as opposed to doing something else?

My parents gave me the wise advice to get a job and support myself. And I’ve done that in one form or another since I was 18. The dream was to live as a writer but I’ve ended up living a life that allowed me to write. Can I call this living a writerly life? Yes, I have not lived a life as a writer, I’ve lived a writerly life.

19 – What was the last great book you read? What was the last great film?

I’ve been reading a lot of fiction. Apparently, I missed the memo that Haruki Murakami is a great writer so I’ve been binge-ing his books. And I just finished re-reading Love in the Time of Cholera by Marquez.

20 – What are you currently working on?

A few collaborative erasures with Rebecca Resinski of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s Sign of the Four appear in Scatterplot. We erased every page of The Sign of the Four(1890) by Arthur Conan Doyle, leaving only four words per page, choosing one word at a time, and alternating the choice between the two of us. In each move we had the flexibility to choose any word anywhere on the page, so the way a finished page reads does not necessarily reflect the order in which it was originally erased. Some of these erasure poems have appeared previously in publications here and there. A chapbook of these collaborative erasure poems, intervals of, will be produced as part of the Errorism series from Ragged Lion Press. Next we’ll likely look for a place to publish the erasure in its entirety.