Description

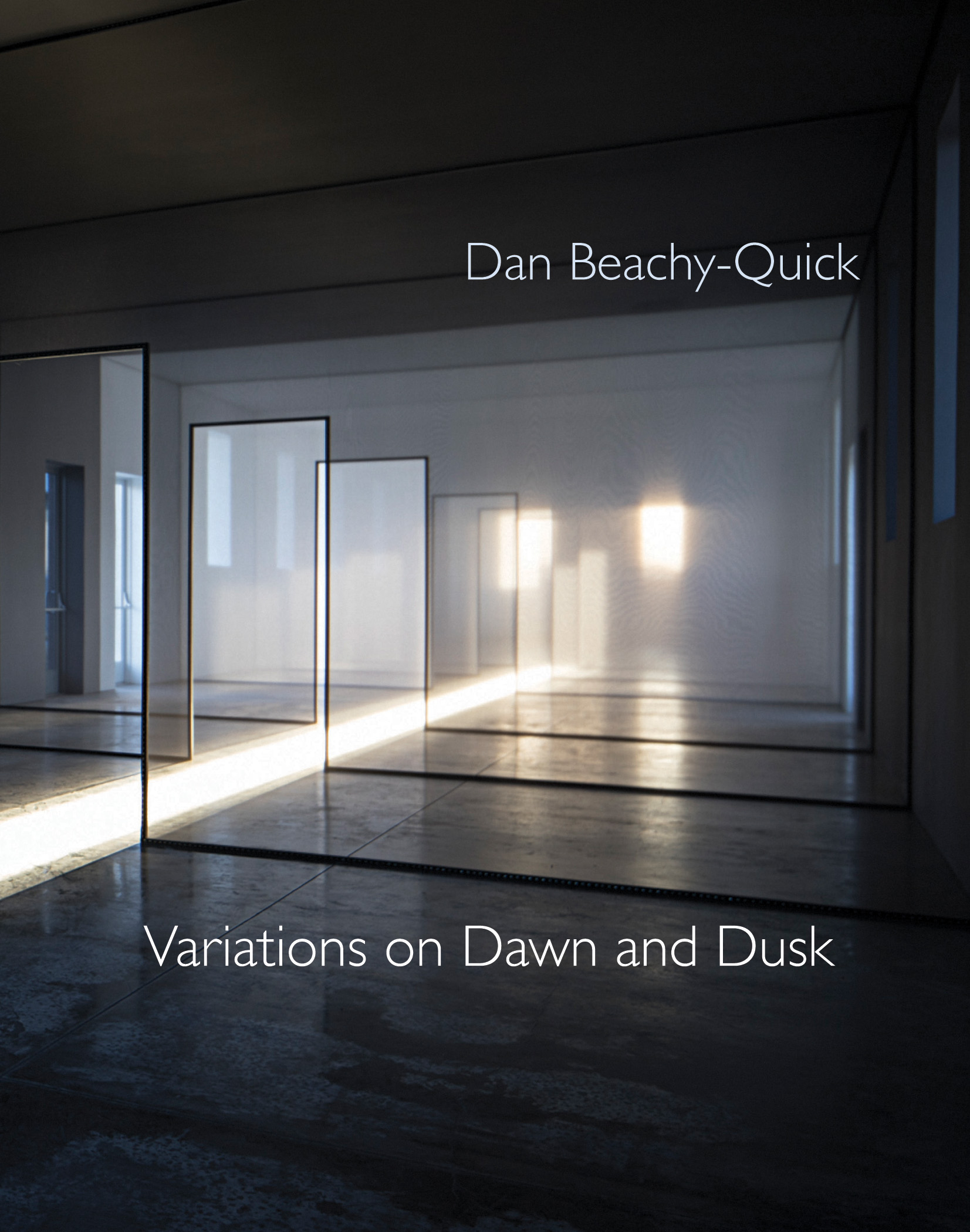

Acting as poetic records of light, the poems in Variations on Dawn and Dusk follow the sun as it warms, cools, colors, and shifts the space of Robert Irwin’s untitled (dawn to dusk) in the desert of Marfa, TX. Built on the footprint of the town’s old hospital, Irwin’s permanent installation is a remarkable structure with walls, windows, and screens that both capture and are taken over by the sun’s changing light. Through this deeply engaged ekphrasis, Dan Beachy-Quick uses language to participate in the overpowering elegance of Irwin’s structure. The poet’s fervent observations lead us in cycles of meditation, moving with the light that slides through the surfaces of the installation. Here, the very foundation of our vision—light—forms the vocabulary from which these poems are built.

Building from Irwin’s use of rhythm and structure, the poems in this collection are constructed with an architectural framework. Rhythmic procedures inversely link the first and last words of the first and last lines of each poem and tie the number of lines to the number of syllables in the first line. These structures form a pattern, a thoughtful consistency through which we are invited to move and meditate with each variation of light.

The spare, untitled poems of Dan Beachy-Quick’s Variations on Dawn and Dusk offer an extended ekphrastic meditation on the book’s cover: an image of Robert Irwin’s windows of light infinitely reflected in a dark room…These poems are about as close to music as you get on the page. Evanescent and beguiling, each poem’s ever-shifting surface, laced with tropes that echo and repeat, by their very poetics articulate the feeling that most have experienced—that what it is to be human is dazzlingly, tantalizingly near, and only through more acute attention to the texture of existence will we finally comprehend it.

1 …I’m delighted to be publishing another book of yours! VARIATIONS ON DAWN AND DUSK will be our second pocket series book with you. These poems can be described with the phrase you use about the site that inspired them; they are, as you say about the physical location: a site of “profound invitation.” Yet this is also true about the poems, as you’ve noted, “the poems form their squares [their shapes upon the page] by certain strict procedures.” Can you discuss the interesting paradoxes and aporias organic to the truth that often “profound invitation” (and I’d add “inspired leaps of insight,” which I see in your work) arise from limitation, from strict and restricted necessities?

Maybe I should begin by saying what inspired the poems—some strange almost instantaneous sense of responsibility—was walking into Robert Irwin’s “Untitled (dawn/dusk)” and seeing 18 squares of light cast down on the dark concrete floor. I stepped from square to square, feeling in each arrival no sequence, no consequence, but the invitation to begin again the very same consideration—though of course, in just those few feet of walking in darkness, the same consideration had already become impossible. It was if each square of light meant one had to learn to see by that light and in that light learn to think again. That feeling, I realized many hours after leaving the building, felt to me the very work a poem requires, and the blank of the page isn’t wholly apart from the blank of light. I also felt this mysterious generosity in the space of the building, this chance to see what we see by, that vision so gently was removed from being merely a means to an end, but was itself the thing being cherished, cared for, allowed to be seen and considered in ways we seldom are allowed or allow ourselves. I wanted to find some equivalent in words, some way to participate in the vision, to create poems that let us feel the space in which thought is possible, and maybe marvel at the miracle of such a thing. Here it is that a poem’s formal life can come to such surprising liberations. Strict form (and here it’s rhyme and syllable and line count all interwoven) creates an invisible frame that might act as does fate. One steps into a space pre-ordained for the possibility of meaning, a hidden grammar undergirding the mind and heart that frees them both from harnessing some “authority” to speak that, in the end, neither might have. I suppose, in its way, it’s devotional work—some trust that what is empty-seeming isn’t empty at all.

2…Speaking of limitation raises in my mind two ideas, I’m hoping you might speak to one or both:

First: working with site specific material: did this mean that you had to stay at the site for the duration of your writing time? If you left, how did you keep re-seeing the work? I imagine a painter who is working with landscape… and I imagine you could come away with photographs, and work from them… but somehow, being there, walking into the site again and again… was this something you did? needed to do? in order to refresh the work in your soul and mind as you continued into the writing’s trajectory?

Second, I want to ask: how is it that you keep the work so vibrantly alive for a reader? Was this something you foreground-ed in your mind, in your creative intention for the work? So many texts begin with such insight, but then they do not continue to inquire, or extend their inquiry, so that one begins to feel one is reading what’s already been explored… in those other texts, the poems don’t continue to enlarge the terrain. Yours do! Can you speak to this in any ways? How and what and why does this occur?

Oddly enough, I only had a few hours at the site, and wrote the poems over the course of many months after that initial experience. Somehow I think it was the form of the poems as a mimetic participation in the Irwin building that allowed me to feel continually vividly present with the concern, and so the writing of the poems themselves became a kind of return to the site, if only intuitively and imaginatively. But there was also something in the first encounter that kept itself vital and alive—as if the direct experience of the place dug down into something more primary in the mind than time, some sense of presence not governed by time, perhaps where art most properly lives. Having that inside me, that symbolic place constantly open, also let me write the poems.

It makes me really happy to hear the poems feel vibrant in that way to you. I think I always hope it can be so for others, but never know if it is or not. I knew they needed to feel so to me, which wasn’t so much a working toward vibrancy, as a trying to stay repeatedly open to the vibrancy of the space—of feeling, of thought, of perception—I felt in Irwin’s work. I did think of each poem as a new beginning, a form blind to its place in the sequence, unable to look behind to know what it might be, unable to look ahead to see what it might become, and maybe it’s the urgency of learning to begin again that offers the poems that vibrancy you see in them. Each poem needs to learn and to see all over again and all by itself, and has such little time to accomplish that impossible work in—kind of like other forms of life I can think of, like our own.

3…I’m always interested in “voice” in your texts, how is the work “sung” by the words, through the words. Can you speak to this text in regard to its pose, its poise, its alignments and fracturings of the voice or voices amassing here? &/or would you speak to this work in the context of your writing’s trajectory, with respect to its voice, its singing? &/or any other aspect of the trajectory of your writing, and how this text moves along and beyond that trajectory?

A strange way to answer such a beautiful question, I fear, but I think I’ve felt for a long time now that there is a music, almost like a grammar undergirding thought, beneath the poem—and maybe the poem is there, in its awkward and loving way, to make that music feel-able, to make it felt. I’m reminded of Hugh Kenner writing about Modernism, and saying “The poem is not the words,” and I feel that is deeply, and ever more so for me, true. Part of me feels as if I’m seeking the right posture in words that can let the dance be felt below them, the right rhythm that lets the music through, and that there is no access to that wordless poem is than the words I build above that dance, that music. All feels glimpses to me, sudden and sometimes peripheral visions, and to stare directly or look too hard would make the vision go away, the sense of that supernal world. I also think the poem speaks as itself, and itself is many others than this I who is me saying “I.” I’ve come to deeply love the anonymous care inside a word, and words strung by love and care and doubt all together, that speaks not of personality, but some more fundamental fate of being exactly this bundle of nerves and experiences who speaks as he can speak. I do feel how words are a consciousness older and more myriad than my meager hold on them, and I suppose I’ve wanted to learn to become a poet who lets those hidden voices speak. It makes me realize, as so many have before, that I have a mouth to sing another’s song.

4… Would you tell me a bit more about you? Anything about you that is not in the bio printed in the book. What you tell me could give insight into aspects of your relationship to this text, or not. Please feel free to offer anything that strikes you to say; anything you tell us will be a gift. Thanks for whatever you are open to offering. I’d love to hear anything that might come serendipitously to your mind.

I was an Art History minor, and actually had planned, when poetry didn’t work out, to pursue a degree in Chinese Art History—but then poetry worked out. I collaborate with a dear friend who is a ceramicist. I’ve helped facilitate for many years a workgroup here at Colorado State called Crisis and Creativity that gathers rangeland scientists and wildlife biologists and community members and alums and current students and poets and artists all together to forge for ourselves a common ground in which real collaboration might be possible. The first result was an art installation tied to models of species extinction that, performed at a science conference on campus, brought people to tears. I’ve been teaching myself ancient Greek for 5 years, and just finished a book project translating poems from 6 poets in lyric tradition. Funny how blank my mind goes on this question. I have 2 children. I’ve been married for 25 years. I coach soccer, play squash, have a slight addiction to exercise. My dog is named Carlo after Emily Dickinson’s dog, and against all common sense we just adopted a cat named Pip. Well, I’m rambling now . . .

5… I know you can’t list them all! But on first thought, on impulse, can you answer: Who are a couple, a few, of the authors, artists, thinkers, workers (in any mediums) with whom you feel a kinship? Who/What comes to mind, just at this moment: who are you reading, listening to, looking at, watching, visiting currently? (You could explain or say something about some of them, if you’d like, which makes this more alive for our readers.)

It’s a long and spontaneous list: Keats, Melville, Thoreau, Emerson; Theognis, Heraclitus, Plato, Parmenides; Guy Davenport, Bach, Susan Howe, Emily Dickinson, H.D., George Oppen, Robert Pogue Harrison, Branka Arsic; my friend Del Harrow’s ceramics; my friend Mai Wagner’s Zen paintings and poems; photos of Pluto from New Horizons; Ezra Pound troubles my mind and also makes it tremble sometimes; Arthur Sze, Forrest Gander; the work of my many students; of course, Robert Irwin. Well, I’ll cut myself short, and only mention that many dear friends and mentors are my constant companions, too, and in some ways I cherish them too much to name them, that it could betray something of what the work is to me. That word you use, “kinship,” feels just right to me. I think what lets the whole cohere is the wide-ranging curiosity, some wild instinct to step into blank territory and trust that thoughts will follow . . . thought that doesn’t repudiate emotion, emotion that doesn’t repudiate thought. Some sense of the poem as made-thing, that has, as Oppen quotes it in his daybook, “a skeptical relationship to words” even as it loves and needs them.

6… You had in mind using an artwork for the cover design, and you worked closely with our cover designer, Cassandra Smith, to bring your vision to light. Could you speak to the artist’s work, and to any aspect of the cover design process?

So luckily, Robert Irwin and the Chinati Foundation, gave us permission to use a photo by Alex Marks of the interior of the building that inspired the poems. It’s really a dream come true, the ideal cover to have for the book. Somehow it seems right to my highest hopes for what the book might be, impossible as the paradox is—that a photo of the inside of the art-work could have within it another inside, and that room within the room are these poems. I love it, too, that the cover has that slant of light that seems to promise a journey through thresholds, and so one can imagine each poems as a single step further—not forward, not backward—but somehow deeper in.

A brief interview with Dan Beachy-Quick

M:

Variations on Dawn and Dusk came out from Omnidawn last year and was longlisted for the National Book Award. Can you talk a bit about this unusual project?D: Much of that book is a deeply private project that I had planned to share with just a few friends. The book came out of living in Marfa for a month. I really fell in love with it. I’d always wanted to show it to my wife, and we decided two summers ago that for our anniversary, we would just get a cheap flight to El Paso and rent a car and go out there for a few days. So, we went to the Chinati foundation, and I was struck by the visceral and aesthetic experience of the Robert Irwin installation

untitled (dawn to dusk), the particular way of being inside this building. The light coming in from the 18 windows was in this kind of perfect square. And I walked from square to square feeling this fundamental element we never think about, by which we see all that we see. And it felt just extraordinarily unexpected and humbling and generous in its ambition to me, and to note that while I stepped into these squares, my body was the thing that was blocking the light. Every square seemed not like a sequence, but a way of having this opportunity to begin again, but begin more truly in some way. We probably spent two hours there and I went away deeply affected. So, I wrote this poem that would try to mimic not just the overall pattern of the building but those squares of light.

M: Did you work on Arrows, out next month from Tupelo Press, alongside it?

D: Yes, Arrows is a group of poems I’ve been writing since around 2011, just very patiently building and thinking through this evolving sense of what I care most about over this lifetime spent writing poetry. During those years, I also started studying ancient Greek and putting myself into a language that, at some level, has at its roots the very source of whatever consciousness and imagination are. Arrows is really trying to figure out how to open up to these very ancient ways of thinking and to ask the questions again that we’ve always been asking.

M: Apart from ancient Greek, are there any other sort of sources of influence that you feel informed the collection?

D: I think because the ancient brings in the political in unexpected ways that the issues that we have with violence and art’s relationship to violence aren’t tied to the particular cultural moment in a way we might think they are. There’s a section in the book of nine poems titled “Drone” that were really written over the summer of 2015 or 2016, during a lot of the escalation of drone strikes in the Middle East. There are poems that are erasures from the New York Times’ drone strike coverage. I was also reading a book on raising bees, because a dear friend had gotten hives. The larger collection is trying to attend to the way in which nature can give us knowledge about itself.

M: You write beautiful essays on poetry (and always seem to be working on multiple projects!). Are you working on any non-fiction at the moment?

D: I just worked on an essay on Moby Dick for a Melville companion that will be coming out, but it’s hard to write prose at the moment. I am two years into working on a new set of poems I’m feeling deeply engaged by, and I’m working on translations from the ancient Greek.

^ back to menu