Hafa Adai Readers,

Thanks for reading from unincorporated territory [lukao]! Welcome to the companion website for the book, where you can find notes, citations, translations, articles, photographs, and other source materials related to the poems. If you have any direct questions, please feel free to contact me via email craigsantosperez@gmail.com). For scholars, I have also included a bibliography of a growing body of scholarship on my work.

Saina Ma’ase,

Craig Santos Perez

[title_divider][/title_divider]This page will be updated periodically up to and following the publication of [lukao] with additional materials.

cover image:

This is the original, color photograph of [lukao] (click to enlarge):

Photograph by Jack Gray, “The Matao New Performance Project at Lasso’ Fuha developing Fanhasso, a contemporary dance directed by Dåkot-ta Alcantara-Camacho at the Festival of Pacific Arts 2016”

~

from the legends of juan malo

—Juan Malo is a young, poor Chamorro man who lived in Guåhan during Spanish colonial occupation. His mischievous adventures (reminiscent of other indigenous tricksters) involved outwitting the Spanish governor and other officials with the help of his carabao (water buffalo). In Spanish, malo means bad.

~

(the birth of Guam)

—I am indebted to the work of Michael Lujan Bevacqua on the “Where America’s Day Begins” slogan. See his dissertation, “Chamorros, Ghosts, Non-voting Delegates: GUAM! Where the Production of America’s Sovereignty Begins” (UC San Diego, 2010).

Welcome to Guam Tourism Videos

~

(the birth of Guåhan)

~

(the birth of Liberation Day)

—I am indebted to the work of Michael Lujan Bevacqua, Christine Taitano DeLisle, Vince Diaz and Keith Camacho on Liberation Day. See Diaz, “Deliberating Liberation Day: Identity, History, Memory, and War in Guam,” in Perilous Memories: The Asia Pacific War(s), edited by Fujitani et al (Duke University Press, 2001): 155-180. Camacho, Cultures of Commemoration: The Politics of War, Memory, and History in the Mariana Islands (University of Hawai’i Press, 2011). A phrase from this poem comes from Christine Taitano DeLisle’s essay, “‘Guamanaian-Chamorro by Birth by American Patriotic by Choice’: Subjectivity and Performance in the Life of Agueda Iglesias Johnston” (2011). Amerasia Journal: 2011, Vol. 37, No. 3, pp. 61-75.

A documentary on The Battle of Guam during World War II

Liberation Day Parade, Guam

~

(the birth of SPAM)

—The information about the Spam Factory comes from the article by Ted Genoway: “The Spam Factory’s Dirty Secret,” Mother Jones, July/August 2011 Issue.

—The tale of vegan Spam comes from the article, “A sister and brother dream of making the perfect vegan Spam,” by Tracy Mumford, Public Radio International (December 29, 2014).

Spam Museum

The Unauthorized SPAM tour

Vegan Butcher Shop

~

from understory

—In ecological terms, “understory” refers to plant life (shrubs, saplings, fungi, and seedlings) growing beneath the canopy of the forest.

~

(i tinituhon)

—“i tinituhon” can be translated as “in the beginning.” Watch a short documentary on the Chamorro creation myth of Puntan and Fu’una:

I Tinituhon from Guampedia on Vimeo.

—“Tumuge’ påpa’” is a common phrase that translates as “writing it down.” However, I also use it to reference Christine Taitano DeLisle’s essay, “Tumuge’ Påpa’ (Writing it Down): Chamorro Midwives and the Delivery of Native History,” in Pacific Studies, Special Issue: Women Writing Oceania: Weaving the Sails of Vaka, 30.1/2 (March/June 2007): 20-32.

~

(p?)

—P?: In the Hawaiian belief system, P? is the creative darkness from which all things emerged.

~

(first ocean)

—RIMPAC: Military term for “Rim of the Pacific Exercise,” the largest international maritime wartime exercise that takes place biannually in the waters around Hawai?i. In 2014, the year my daughter was born, twenty-two nations participated in RIMPAC. For more on RIMPAC, see http://hawaiiindependent.net/story/we-need-to-ask-hard-questions-about-rimpac.

~

(first ultrasound)

—“E, Pele e” is a line from Haunani-Kay Trask’s poem “Night is a Sharkskin Drum.”

~

(second trimester)

For more about the use of pesticides and the growing of GMO crops in Hawai?i, please see the documentary: Islands at Risk

Part 1

Part 2

Part 3

For information on the use of Pesticides in Hawai?i, please watch this short animated info-documentary, “Pesticides in Paradise: Hawai?i’s Heath and Environment at Risk,” produced by the Hawai?i Center for Food Safety.

~

(first teeth)

—Kollin Elderts was an unarmed 23-year-old Hawaiian man who was shot and killed by a drunk, off-duty, haole federal agent in a Waik?k? McDonalds during the 2011 APEC meeting, held in Honolulu. The agent was acquitted of this murder, and many activists have compared this act of violence to other acts of violence against brown and black men in the continental United States.

—APEC stands for the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation, a conglomerate of politicians and corporations that are negotiating the Trans-Pacific Partnership, a free trade agreement agreement that has been described as “NAFTA on steroids” for the Asia-Pacific region.

~

(third trimester, january 27, 2014)

—Enewetak, Mororua, Hiroshima, Nagasaki, Trinity, and Bikini are all places that have been devastated by nuclear weapons. In 1954, Guam was exposed to high levels of Strontium-90 because the island was “downwind” from nuclear detonations in the Marshall Islands. Currently, Chamorro activists and politicians are advocating for the inclusion of Chamorros in the “downwinder” category of the Radiation Exposure Compensation Act.

~

(papaha?naumoku and wa?kea)

—In Hawaiian genealogy, Papa is Earth Mother and W?kea is Sky Father. They meet atop Mauna Kea, which is the highest and most sacred mountain in Hawai?i. Their first born child, H?loa, is still born, so they plant his body, from which grows the kalo (taro). Kalo is an important food in the Hawaiian diet because it is considered an ancestor of the Hawaiian people. Poi is made by cooking and pounding kalo and mixing it with water.

—The “TMT” is a Thirty Meter Telescope that is proposed to be built atop Mauna Kea. Many people are protesting its construction because it will desecrate the sacred mountain. For more on the protests, please visit: http://www.protectmaunakea.org/. See also “Inside the Fight against a massive telescope atop a sacred Hawaiian mountain.” https://www.vice.com/en_us/article/inside-the-fight-against-a-massive-telescope-atop-a-sacred-hawaiian-mountain

A short video on Mauna Kea from Living Ocean Productions:

~

(santa marian kamalen)

To learn more about Santa Marian Kamalen, watch this documentary, “Voices of Our Elders: Santa Marian Kamalen Retold,” featuring Toni “Malia” Ramirez, and produced by Guampedia:

Santa Marian Kamalen Retold from Guampedia on Vimeo.

~

(first birthday)

—“The rape of oceania began with Guam” is a phrase from The Pacific Islands (1951) by Douglas Oliver, and refers to the fact that Guam was the first Pacific island colonized by Europeans.

Listen to “na? ma?hele o ke kino”:

~

from organic acts

—The title of this poem historically refers to The 1950 Organic Act of Guam. Previously, Guam was an unorganized, unincorporated US territory governed by the US Navy. A civilian government, administered by the Department of the Interior, was created through the 1950 Guam Organic Act, and US citizenship was granted to island residents. The Organic Act also lists the land and acreage that the US military would continue to control and occupy—nearly 30 percent of the 212-square-mile island. This includes “real property,” as well as ‘tidelands’ or “submerged lands,” lands permanently or periodically covered by tidal waters. Military fences become the teeth of the giantfish. Read the Organic Act here: http://www.guampedia.com/the-organic-act-of-guam/

photo credit and description:

President Harry S. Truman (seated) signs the Guam Organic Act of 1950. Credit: Harry S. Truman Library and Museum.

—Stories of the giant fish can be found in Mavis Warner Van Peenan’s Chamorro Legends on the Island of Guam (U of Guam: Micronesian Area Research Center, 1974) and Eve Gray’s Legends of Micronesia: Book Two (Honolulu: Trust Territory of the Pacific Islands, 1951).

—For a translation of the Chamorro rosary, see “Rosario’s Rosaries: The Rosary Prayers in English and Chamorro” (2008): charoanderson.com/rp-engcham.html.

Listen to the Chamorro rosary here:

—For more on the kantan chamorrita communal poetic form and its connection to the Chamorro rosary, see Laura Souder, “Kantan Chamorrita: Traditional Chamorro poetry, past and future.” Manoa 5(1), Writing from the Pacific Islands (Honolulu: U of Hawai’i Press, 1993) and Judy Flores,”Kantan Chamorrita revisited in the new millennium” in Transnationalism and Modernity in the Music and Dance of Oceania: Essays in Honour of Barbara B. Smith. Lawrence, H. (ed.). Sydney: University of Sydney, 2001: 19-31.

Short Documentary on Kantan Chamorrita

Kantan Chamorrita from Guampedia on Vimeo.

—To listen to audio samples of Kantan Chamorrita, go here: http://www.guampedia.com/kantan-chamorita-2/

—The quatrain that ends each excerpt of “from organic acts” is a verse from the chamorita higai (thatching chamorita), which could be heard when village communities gathered to thatch the roofs of homes. See Carmen I. Santos, “Guam’s Folklore,” in Umatac by the Sea: A Village in Transition, edited by Rebecca Stephenson and Hiro Kurashina (Mangilao, Guam: Micronesian Area Research Center, 1982): 130.

—Maria Yatar from “Navigating Modernity,” presentation at the 16th annual Guam Association of Social Workers Conference (1995): n.p. Quoted in Lilli Perez, “An Ethnography of Reciprocity Among Chamorros in Guam (Ph.D. dissertation, Bryn Mawr, 1998): 36.

—For more background on “from Organic Acts,” see my essay “from Organic Acts: Tsamoria, Rosaries, and the Poem of My Grandma’s Life” (Life Writing Vol. 12, No. 2, 2015: 225-230.)

—Read more stories of Guam War Survivors here: http://guamwarsurvivorstory.com/

Video documentary on Guam War Survivors:

Part 1

Part 2

Part 3

Part 4

Part 5

~

from Ka L?hui o ka P? Interview (September 27, 2014)

—Thanks to Kalei and Pua for conducting this interview with us at Ho?oulu ??ina. For more about the birthing class for Hawaiian women, visit the website: https://www.rootskalihi.com/ka-lahui-roots-kkv/.

Watch a clip of the documentary Pattera: Midwives of Guam (1991) produced by Karen Cruz:

Pattera from Guampedia on Vimeo.

—The history of Chamorro midwives comes from several sources: See Karen A. Cruz, The Pattera of Guam: Their Story and Legacy (Guam Humanities Center, 1997) and Christine Taitano Delisle: “Delivering the Body: Narratives of Family, Childbirth and Prewar Pattera” (M.A. thesis, University of Guam, 2000).

—“Placental Politics” is also from Delisle: “A History of Chamorro Nurse-Midwives in Guam and a ?Placental Politics’ for Indigenous Feminism” (Intersections: Gender and Sexuality in Asia and the Pacific, Issue 37, March 2015). She defines it as:

“Placental politics, as I see it, names a history and a future by which indigenous women have consciously chosen to act as stewards of Chamorro peoplehood and Chamorro place. In Guam’s history, Chamorro women’s practice of planting the placenta and the cord that connected and nourished a newborn to his/her mother was also a practice that connected indigenous Chamorros to the land in order to ensure proper growth and directionality. Implanted in their own struggles against reckless development and militarisation, contemporary Chamorro women activists also continue to care and steward Chamorro peoplehood and land in efforts to keep things right and balanced, and to sustain what is maolek.”

~

from the island of no birdsong

—Information on the Micronesian Kingfisher, as well as the “Estimated Time of Developmental Markers” that I quote from can be found in the Micronesian Kingfisher Species Survival Plan: Husbandry Manual, 1st edition, edited by Beth Bahner, Aliza Baltz, and Ed Diebold (1998).

Micronesian Kingfisher, Cincinnati Zoo

San Diego Zoo

Philadelphia Zoo

St Louis Zoo

Chicago Zoo Staff Handrear Micronesian Kingfisher chick

Micronesian Kingfisher Chick Hatches at Smithsonian’s National Zoo

Micronesian Kingfishers Return Home

Endangered Micronesian Kingfisher gets help from Uncle Sam

—The quote from L.C. Shelton, former Curator of Birds at both the Philadelphia and Houston Zoos, and leader in the establishment of the Guam Bird Rescue Project in 1983, can be found in his article “Captive Propagation of the Micronesian Kingfisher” (The Philadelphia Zoo Review, 2(2) 1986: 28-31).

—The two passage about the birth of Micronesian Kingfishers come from: William Mullen, “One of world’s most endangered species, Guam kingfishers live on in zoos in struggle to survive,” Chicago Tribune (June 27, 2010); and Press Release, “Micronesian Kingfisher Chick Hatches: Total of 129 Birds in Existence,” (Smithsonian National Zoological Park, January 24, 2014).

The Last Female Marianas Crow on Guam Dies

—For more on the Marianas Crow, see the Draft Revised Recovery Plan for the Aga or Mariana Crow (U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, May 2005).

—For more on the population explosion of spiders on Guam, see Christopher Joyce, “Hungry Snakes Trap Guam in Spidery Web” (NPR, September 19, 2012).

Brown Tree Snakes Help Spiders Overrun Guam

—The spelling of the Micronesian Kingfisher bird voice (kshh-skshh-skshh-kroo-ee kroo-ee kroo-ee) and the Mariana Crow bird voice (kaaa-ah kaaa-ah) were found on the Handbook of the Birds of the World Alive website (http://www.hbw.com/).

Guam Tree Snakes impacting island’s Forests

—The passage about the Fire Tree is from 36th Civil Engineer Squadron, “Volunteers help save endangered tree” (Air Force Print News Today, November 13, 2012).

—As stated on the Pacific Islands Club resort website, the goal of their Micronesian Kingfisher mascot, Siheky, is to “preserve and increase awareness for this species by creating a mascot that not only serves as an iconic symbol, but also creates familiarity with the near extinct bird.” http://www.picresorts.com/ourMascot-en.html.

—According to the ancestral thirteen-month Chamorro calendar, the first day of February marks the new year. On that day in 2014, Chamorro cultural groups, Our Islands are Sacred and Hinasso revived the lukao fuha, the annual procession to Fouha rock to honor Fu’una and Puntan, a customary practice that had not been enacted for hundreds of years. This revitalized tradition marks a return to our birth stone, a re-birth of our creation story, our first story.

—“hinasso” can be translated as “imagination, thought, memory, or reflection”

—“o asaina, o aniti” come from Peter R. Onedera’s poem/chant, “O Asaina,” and translates as “o ancestors, o spirits. The chant calls on the ancestors to protect us.

~

from Mahalo Circle

For more on Kokua Kalihi Valley Ho?oulu ??ina, see the short documentary:

Many of the Maui farms and grocery stores in this poem are featured in a documentary about sustainability on Maui. As a final project for the Huliau Youth Leaders program, seven Maui teenagers spent the first week of their summer living together on a farm and eating only food grown on Maui for four days:

To learn more about water rights on Maui, see the Ola I Ka Wai: Water is Life documentary:

For more about Ma?o Farms, see this TEDx Talk by Kamuela Enos, the Director of Social Enterprise at Ma?o Farms, titled “Working Collectively to restore ancestral abundance”:

For more about Daniel Anthology of Mana Ai, see his Tedx Talk, “What you put in your mouth can change the world”:

Homestead poi

De-processing Spam event

M?noa Community Garden

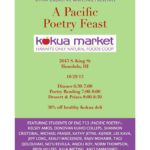

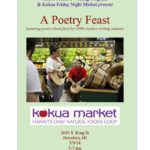

Kokua Market Poetry event

Wedding pics

*

Selected Bibliography

Katherine Baxter and Lytton Smith. “Writing in Translation: Robert Sullivan’s Star Waka and Craig Santos Perez’s from unincorporated territory.” Literary Geographies (2.2) (2016): 263-283.

Briggs, Robert J. “There’s no place (Like Home): Craig Santos Perez’s poetry as military strategy.” Green Letters: Studies in Ecocriticism (2016).

Cocola, Jim. “Forget your Pastoral: Haunani-Kay Trask and Craig Santos Perez,” chapter in Places in the Making: Cultural Geography in American Poetry (University of Iowa Press, 2016).

Heim, Otto. “Locating Guam: The Cartography of the Pacific and Craig Santos Perez’s Re-mapping of Unincorporated Territory.” In New Directions in Travel Studies (Palgrave 2015).

Bevacqua, Michael Lujan. “The Song Maps of Craig Santos Perez.” Transmotion 1.1 (2015).

Schlund-Vials, Cathy J. “?Finding’ Guam: Distant Epistemologies and Cartographic Pedagogies.” Asian American Literature: Discourses and Pedagogies 5 (2014): 45-60.

Woodward, Valerie. “I Guess They Didn’t Want Us Asking Too Many Questions: Reading American Empire in Guam.” The Contemporary Pacific 25.1 (Spring 2013): 67-91.

Clark, Ryan. “The Appositional Project: Craig Santos Perez’s from unincorporated territory [saina].” Spoon River Poetry Review, 11/10/13. Web.

Hsu, Hsuan. “Guahan (Guam), Literary Emergence, and the American Pacific in Homebase and from unincorporated territory.” American Literary History (Summer 2012) 24: 2.

Lai, Paul. “Discontiguous States of America: The Paradox of Unincorporation in Craig Santos Perez’s Poetics of Chamorro Guam.” The Journal of Transnational American Studies, Volume 3, Issue 2, 2011.