Description

Witness to the late and sorrowful pact between predator and prey, spectator and species, Molly Bendall’s fifth book beckons the reader into the enigma of animal relation. “What’s left?” she asks. The answer is past remembering, attuned to extinction. Forsaking the names of creatures, Bendall returns like a sleepwalker to a painted habitat of swamps and savannahs, of captivity and display. At once playful and melancholy in its sifting of ritual discretion and shame, Watchful brings every sense, every measure, to bear on the blood mirror of the human.

Over the years Molly Bendall has been writing luminous and illuminating poetry. Bendall’s work is always full of a high-stakes daring, coupled with the joys of sonic intensity. Her exquisite new book, Watchful, takes us further, unveiling both the disquiet and the beauty of our contemporary moment through song. As she boldly writes: “I come here to teach my ear to adore, shape myself as orphan.”

Peter Gizzi, author of IN DEFENSE OF NOTHING: SELECTED POEMS, 1987-2011

How do we look now/In the roped-off area?” A zoological refraction, Watchful asks how we see from within the structures we’ve built to separate ourselves from other animals. The Watchful gaze tracks non-human animals in captivity as well as the oblique, dazzled human-animal lens that observes them. And it takes stock of the resource-oriented thinking that has remade the world for both kinds of animals. Bendall’s long poem “The Sixth Wave” meditates damningly on techno-capitalist optimism and the climate crisis that is the cause of the sixth great extinction: “The entire/Pride blurring/Across the rock face.” Watchful is a brilliant and timely book: hard-edged, witty, resplendently pictorial, and furious.

Cathy Wagner, author of NERVOUS DEVICE

To have here in Watchful one of our most trusted beholders now giving her attention, spirit, and musical powers to that place of incomprehension animals and humans inhabit together is outrageous and beautiful. Molly Bendall is one of our most expansive poets and the constant alliances being made between her and other beings is something everyone should see. She is all the world’s gift.

Peter Richards, author of NUDE SIREN

About the Author

Reviews

Excerpt

Molly Bendall is the author four previous collections of poetry, After Estrangement, Dark Summer, Ariadne’s Island, and Under the Quick. She also has co-authored with the poet Gail Wronsky Bling & Fringe from What Books. Her poems and translations have appeared in many anthologies, including American Hybrid and Poems for the Millenium. She has won the Eunice Tietjens Prize from Poetry, The Lynda Hull Award from Denver Quarterly, and two Pushcart Prizes. Currently she teaches at the University of Southern California.

A brief interview with Molly Bendall

Conducted by Rusty Morrison

WATCHFUL begins with a deeply moving quote from Jean-Christophe Bailly’s THE ANIMAL SIDE. “In no way had I entered that world; on the contrary, it was rather as if its strangeness had declared itself anew, as if I had actually been allowed for an instant to see something from which as a human being I shall be forever excluded.” Would you speak to what prompted you to choose this quote as a gateway into this text—taking into consideration some of the insights it suggests, which a reader may meet in these pages? And, perhaps you can say a little about what this quote may not prepare a reader for in this text? What more is encompassed in the scope of this courageous compelling work, fierce in all that it confronts?

In the book The Animal Side (translated by Catherine Porter) Jean-Christophe Bailly reflects on animal relations by looking at art, literature, and philosophy and considering our shared space with animals. Before I discovered this book, I had been spending time at the LA Zoo where I began taking notes and meditating on my own responses to the space.

The L.A. Zoo is a very large area full of huge trees and beautiful foliage and the various enclosures and habitats for animals. I became interested in what this space and the encounters with animals elicited from me. I felt enthralled and a sense of pleasure in their presence and in looking at them, but, at the same time, I also felt a sense of guilt and shame at my complicity in their plight as captives. The zoo creates a strange and uneasy position for me to occupy. The close proximity to wild animals and the variety of them in one place is utterly artificial. They are completely estranged from their natural habitat and so am I. I was a spectator and they the spectacle. And, yet, this could also be the other way around. I am being seen by them. In addition I am seeing myself reflected in them. And ultimately, both of us are observing the space around us. This complex entanglement of “watching” was compelling to me.

Bailly also says, “the world in which we live is gazed upon by other beings.” I’m intrigued by the idea that we and our environment are being watched and monitored by living things that are unlike ourselves. We humans are not the only beholders.

I also felt a powerful elegiac sense while working on these poems. In the zoo the animals had lost their native existence, their freedom. Evident as well is the threat of their vanishing from the earth by the fate of extinction. John Berger, the art critic and novelist, says in his book, Why We Look at Animals, “The zoo to which people go to meet animals, to observe them, is, in fact a monument to the impossibility of such encounters.” This idea is startling also—that the animal is, not itself, but a specter of its former self.

Finally, though, when I took walks in the contrived space of the zoo and came upon animal after animal, I wanted to retain some sense of encountering them anew, to keep a strangeness about them and the place. That’s why I decided to keep them nameless in the poems. Their habits and movements were fascinating to me and sometimes those observations found their way into the poems.

I want to tell you that it is for me personally a thrill to be publishing WATCHFUL, which is the first book of yours that will come from Omnidawn. But of course you have a strong record of previous publications. I have been a reader of yours for some time, and many of your past books remain important works for me personally because of your deftly drawn images that are as concise as they are mysterious in the ways that they refract so many subtle auras of meaning. It is exciting to see you turn your attention to the subject matter of WATCHFUL. Your astute and intelligent observations demonstrate great poise, the compression of your diction creates in the reader a hyper attention, a powerful “watchful”ness.

Here are a few lines from the first poem that offer a small glimpse of your ability to bring a sly humor to your play of diction, your positioning of figure—a reader can gain some small sense of how much there is to watch for.

They’re myth because

we slept so long. What lulls us besides the North Star?

Now comes the broadcast

and reassurance. Lean back into everydayness

while some just swan by with the last

of their hardened expression.

And the wonderful elasticity of your grammar that heightens our attention to language as material presence:

A bit of weed and was can make

them elegant.

Of course, the title’s significance is so much larger than a reference to your dexterity, the surprises in your use of language. But I wanted to raise the ways that I see your formal relation to the text reflected in the title, and how your form liberates meaning to arrive through more than the content, more than from the subject matter alone. I wonder if you could speak to the crafting of the your poems, and how your work has evolved. I understand that you trained as a ballet dancer. Do you sense a kinship between this and your use of the line, your relationship to image?

To answer the question about my own sense of language in a poem, I would first mention three poets who have meant a great deal to me over the years and still provide inspiration and examples: Theodore Roethke (in particularly the poems from Praise to the End), Medbh McGuckian, and Barbara Guest. One aspect their poetry modeled for me was a verbal intricacy and surprising “arrangements” of language inside of a poem. Their poems refashion logical syntax, and, also, by often utilizing catechresis, the poems unfasten words from their familiar roles and relationships.

I like to use the phrase “misbehaving” poem to define certain qualities of poetic language. This term not only suggests subverting the rules and the utilitarian aspects of language, but it implies rebelling against and undermining a social expectation. I want to incorporate a sense of mischief which probably emerges as wit. Shifts in address and changes in the speaker’s position are also devices I’m compelled to use. I would say my training in dance comes into play here. Early on, dance provided a way of thinking about art and how it can enact or insinuate various tones, and psychological tensions without necessarily pointing to specific content.

The idea that a non-verbal art form can have things in common with a verbal one is fascinating to me. I am drawn to poems which move through various modes of perception and can fluidly (and not so fluidly) go back and forth from interior realms (movements of the mind) to the exterior, physical world. I’m interested in how poems (like dance) can defy normative temporality—reversing, suspending, pulling in, and unfurling.

I’d be grateful if you chose a point in the manuscript, perhaps a section of particularly powerful significance for you, or that was especially difficult for you, and then discuss why. What experience or convergence of experiences initiated any particular aspect of this work that might be fruitful to discuss? What did the writing of that part of the manuscript demand of you? Change in you? And/or you might focus part of the book that surprised you or frightened you because of what it demanded from you.

Two sections of the book consist of long poems, “Grassland Bureaucracy” and “The Sixth Wave.” I would say these two poems were particularly challenging for me to sustain. Moving urgently and breathlessly and to push provocation more, even with a sense of both fury and wit, was something I wanted to do with these. I wrote them in slim lines and mostly eliminated punctuation. I stitched together and overlapped images, historical and temporal planes, and multiple tones, then set them moving at a faster pace.

In the final sequence of the book, “Currents,” I wanted to try another mode of the elegiac. I thought of particles of sound and partial thoughts becoming audible and surfacing out of a larger form. I like the idea of some scraps rising up through little apertures in the fabric—ones that might still attempt to convey something with a sense of urgency, as they are being pulled or submerged.

Could you talk about any writers &/or artists &/or thinkers who have influenced you in this work? (in what direct or indirect ways have you felt this occur?) And/or could you talk about who are you reading currently? With whom do you feel a kinship or a provocation or…?

I have been reading many books over the past few years which are engaged with animal relations and ecological concerns. I want to mention mostly the poetry books that have meant a great deal to me: Inger Christensen’s Alphabet, Juliana Spahr’s Well Then There Now, Oni Buchanan’s Must a Violence, Simone Muench’s Wolf Centos, Suzette Bishop’s Hive Mind, Lucas de Lima’s Wetland, Jody Gladding’s Translations from Bark Beetle, and, finally, exquisite essays by Amy Leach from her book, Things That Are.

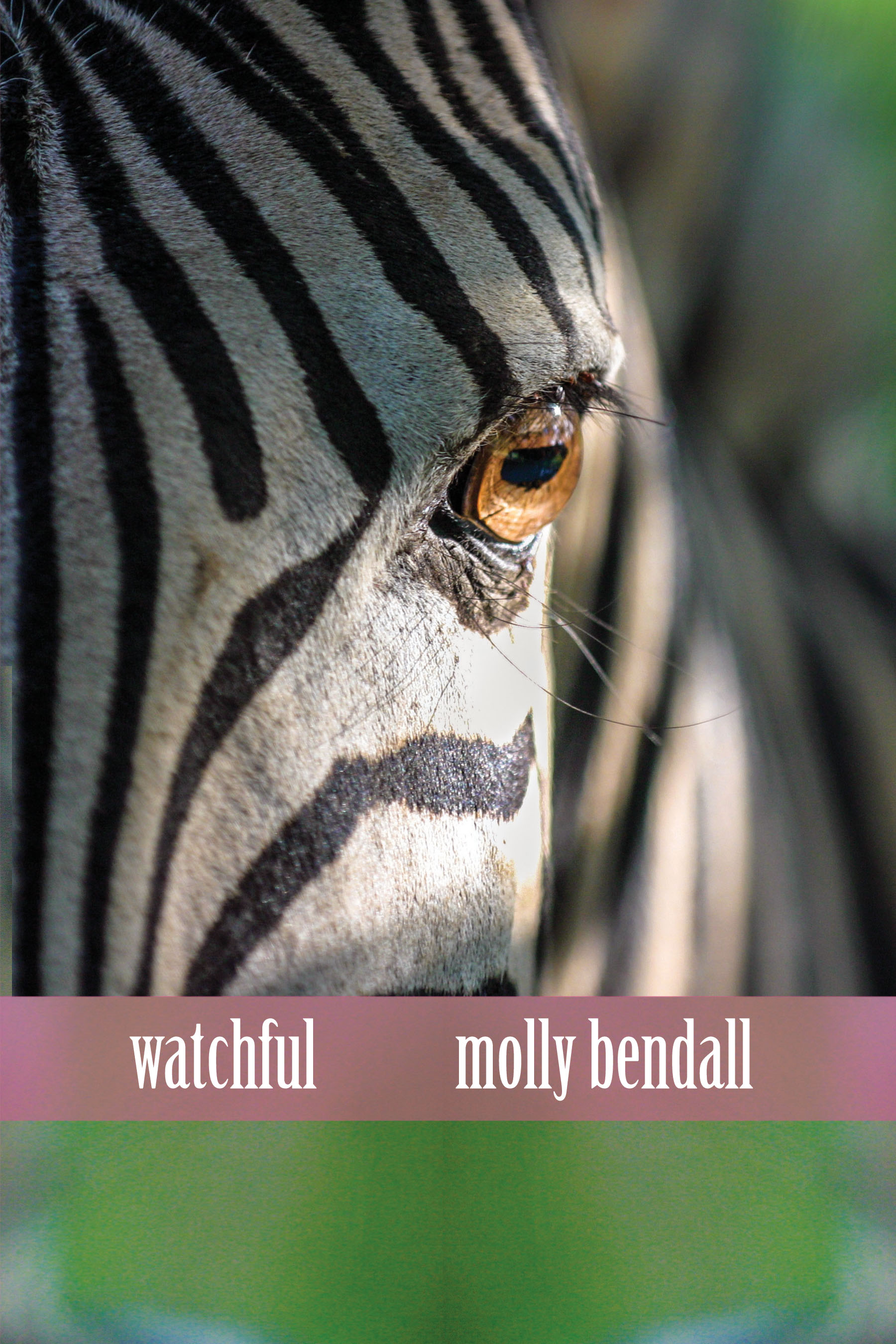

You selected the image that we used in the cover design for this book. Would you describe your considerations regarding the cover image? How does this cover align with your intentions for the text?

I came across this image online when looking at wildlife photography. I love the disarming proximity of the face, the intense dark paths of stripes, the blur of green in the background, and, of course, the zebra’s magnificent eye.

I’d like to quote Bailly again who considers the gaze in this way: “The gaze gazes, and the unformulated is, in it, the pathway of thought, or at least of a thinking that is not uttered, not articulated, but that takes place and sees itself, holds itself in this purely strange and strangely limitless place which is the surface of the eye.”

Flinchingly inhabiting a human gaze haunted by extinction, capitalism, carceral impulses, and environmental crisis, Bendall’s spare lyricism interrogates the tense but tender kinship between human animals and their strange and estranged cohabiters of an endangered earth.

Molly Bendall’s new book, Watchful, sparkles with sagesse, a “knowingness” of animal wisdom. At the same time, there is a current of unknowingness and mystery here that runs counter to intuitive “animal” knowledge – as the collection’s epigraph has it: “something from which, as a human being (I) shall be forever excluded.

Molly Bendall’s Watchful is a gathering of spirit and song in honor of the animal world. She reminds us that the animals we see also see us. Bendall is one of our most wise and necessary poets, and her work is a portal to the truly spiritual aspect of our human relationship with animals.

While the root of Bendall’s poetics is found in modernist fragmentation, her strategies of interruption and dislocation of subject, narrative, and syntactic position are part of the contemporary literary conversation. She also owes her style and themes to a feminist poetics fueled by a sense of exclusion from culture and nature.

Trespass

A glance into the gray, stuttering and flushed.

It’s most like treachery except scales

come shedding. I’ll wear the fatal expression of being somewhere else.

Tumbled in a dizzy

habitat, scattershot and rigged with watchers.

And young crawl blindly—fuzz striping, nubs for horns.

Their eyes, evening clocks, and a milky way. Still stunned

at the clouds bearing down.

Understand the lure. Thrumming

with green current, love’s sort of in a thrall.

I woke to this civic arrangement, peered

down the tunnel.

Heavy in their entourage, they secure a chilly saga,

always for each other, while

I daughter myself, I girl the most

delicate ones, creep up to them nearer the forelocks and swarming flies.