Description

quiet orient riot is an exploration of the tendons of motherhood, its mutinies and munificences. It is also a book of births and the politics of birth-regimes. Recounting a journey to bear a Palestinian child in the occupied Palestinian territory, the poems conjure up maternity as forecast, tally, weapon; its many filtrations through liturgical command and demographic anxiety. Maternity is made possible through contingent access to Israel’s sophisticated fertility treatment infrastructure, and impossible as it coincides with Israel’s 2009 assault on the Gaza Strip. What kind of language, then, can hold a body inside a body through emergency, diminishment, and into resistance and bloom? What kind of language might hold precarious humanhood?

Most significantly, quiet orient riot asks of itself, without release or relief: can a text seek linguistic disorientation and reorientation both? Can a text walk the tightrope from detail to detail so as to envision a kind of awareness that is kin to worship? quiet orient riot does not shy away from a word like “worship.” Nor does it shy away from how such worship might manifest in the words of a poem, bowing to a “chirpy printed sound” in Palestine and a forest of “little justices.”

Urgent and open-hearted, this absorbing debut collection has Khankan musing… political observations are framed by the personal: the poet’s aim to have a child, as her struggles with fertility… parallel but are never reduced to an awareness of her community’s declining birth rate. “Count this child girl | count her on this side” she proclaims in poems celebrating motherhood just as she celebrates her homeland: “cumin is pervasive…colors erupt & recline against rocks & thyme.” VERDICT Written in a sort of disciplined stream of consciousness, with pipes instead of line breaks and titles embedded in capital letters, this work will attract a broad cross-section of readers, whether their concerns are politics, parenting, or poetics.

Barbara Hoffert, Library Journal

Nathalie Khankan’s “Quiet Orient Riot” is a generative and lyrical read… a deeply personal poetic narrative that traces her journey toward motherhood in the midst of demographic and territorial crises… The poems of this collection talk to each other, like neighbors carrying on a conversation through open, opposite-facing windows across the street. Snatches of conversation are often lost, and the poems and the people they discuss retain a certain atmosphere of mystery… The resonances are eerie: missing mothers, colonized homelands, sex industry workers who only come to light in the dark…It is a journey infinitely worth taking.

Blue Fay, The Daily Californian

(4/20/20)

An interview with Nathalie Khankan

(conducted by Gillian Olivia Blythe Hamel)

I’m thrilled that Dawn Lundy Martin selected quiet orient riot as the winner of the Omnidawn 1st/2nd Poetry Book Prize. This book was so striking to all of us who read for the contest with its clandestine delicacy, its sense of imminent er/irrupture, that its taut language may foment and flower at any moment. I wonder if you could speak more conceptually about how this book came to be?

The bulk of the poems in this book were written in disparate intervals between 2013 and 2017. It was a writing that was “struck by safety.” I borrow this expression from Syrian dissident writer Yassin al-Haj Saleh. My husband and I had to leave Palestine in 2012 after almost eight years living and working in Ramallah. We didn’t leave willingly. Collapsing that home, that forced departure was a gutting experience. Our daughters, both born in Bethlehem, Occupied Palestine, were two and three years old when we landed in San Francisco. I had a fresh green card. The man in US passport control smiled. He bid us Welcome Home.

Later, and since then, and as the girls would slowly lose the sing-song of their first colloquial, I was looking for adequate language to tell them in as complete a syntax as I could, as exactingly as possible, where they were born. That was so important for me then and continues to be so because it’s a story much larger than them of course. They are, also, Palestinian children born on Palestinian soil but they can’t be recognized as such. The absurdity and tragedy of the circumstances surrounding their conception—conceived through privileged access to an Israeli fertility clinic that coincided with the Israeli 2009 assault on Gaza—are extreme, and yet so mundane in the settler-colonial reality of Israel/Palestine. Then, of course, you have the plethora of interweaving Holy Land mythologies and histories surrounding birth, motherhood, reproduction, erasure and resistance. All that is a hard animal to draw but I wanted to try. And to make it clear at the same time why we didn’t want to leave, how we couldn’t possibly leave, because we were already completely home. Conceptually, then, the book is a cognitive map/imaginary of a birth and birth place, but also of an emergence and an emergency.

The shape of these poems have such a photographic intensity, splintered with caesuras, with the titles sprouting up within the lines themselves. What concerns around form began to assemble as you wrote this book, particularly as you moved through cultures and borders as you worked?

As it were, the whole riot, all the poems in quiet orient riot were written after “the big move” or movement from Ramallah through Copenhagen to San Francisco had taken place. I was firmly landed in San Francisco when I began to write these poems but in severe aching for the home we couldn’t remain in. I wasn’t writing narrative poems but so much insistent story and biographical and documentary detail leaked through. And so I was looking for a form that would be firm yet yielding enough to allow narrative while containing it. I wanted a quiet spill not the torrent of it.

The poems I had been writing since landing in San Francisco were far between Palestine poems. I didn’t realize until much later just how tightly and tenderly they were in fellowship with each other. After writing a little series of short prose poems with caesuras that inhabited only the upper third of the page, something about the form felt arrived, made me curious. I decided to try that form out on older poems and began rewriting them in this form, breaking up longer poems, and coaxing even poems that were graphically expansive on the page into a little square. It was liberating to be in that container and writing flowed more easily from there, flowed more easily into it. In that sense, it was form that allowed for companionship, for me to recognize it between the poems I had already written and between old poems and the ones I needed yet to write.

Here’s the space to talk about anything/one that might have influenced this work. Perhaps you could also tell us what you’re reading/watching/listening to right now.

To name a few: Etel Adnan, Ghassan Zaqtan, Adania Shibli, Hussein Barghouthi, Mahmoud Darwish, Larissa Sansour, Asta Olivia Nordenhof, Adrienne Rich, Carolyn Forche, Craig Santos Perez, Maggie Nelson. I’m reading Muriel Rukeyser, finally. Lebanese Etel Adnan’s poems and writings are foundational texts to me and have sustained me on three continents, especially the riveting cartographies of The Arab Apocaplyse, and In the Heart of the Heart of Another Country. Palestinian artist Larissa Sansour’s video art with Søren Lind is dystopian yet gorgeously evocative. There’s that moment in her beautiful and terrifying and beautifully terrifying short sci-fi film In the Future They Ate from the Finest Porcelain (2016) where the narrator says, “the Apocalypse is never that single cataclysmic event. It sneaks up on you.” Full of radical possibility, her films so movingly upend the idea that Palestinians’ contemporary reality—the injustices and unbearables of it— is irreversible, indeed the idea of any disenfranchised community’s reality as a given.

Is there anything you’d like to add by way of autobiography—anything from your personal life, beyond/outside your writing life—that might be of interest to readers, or might give them another angle of insight into your work?

My mother was a Finnish immigrant, my father a Syrian refugee. They met in Copenhagen and settled down there. I grew up in Denmark then, inside Arabic, Danish, and Finnish, in the intersection of three language families. I always wondered about mother and father tongues and other tongues. In an early memory I would sing along to F. R. David’s hit song “Words Donkomisy.” It was such an irresistible love song and donkomisy seemed to me then such a perfectly round and whole word. Until by chance I began to separate the sounds. Words Don’t Come Easy. They still don’t!

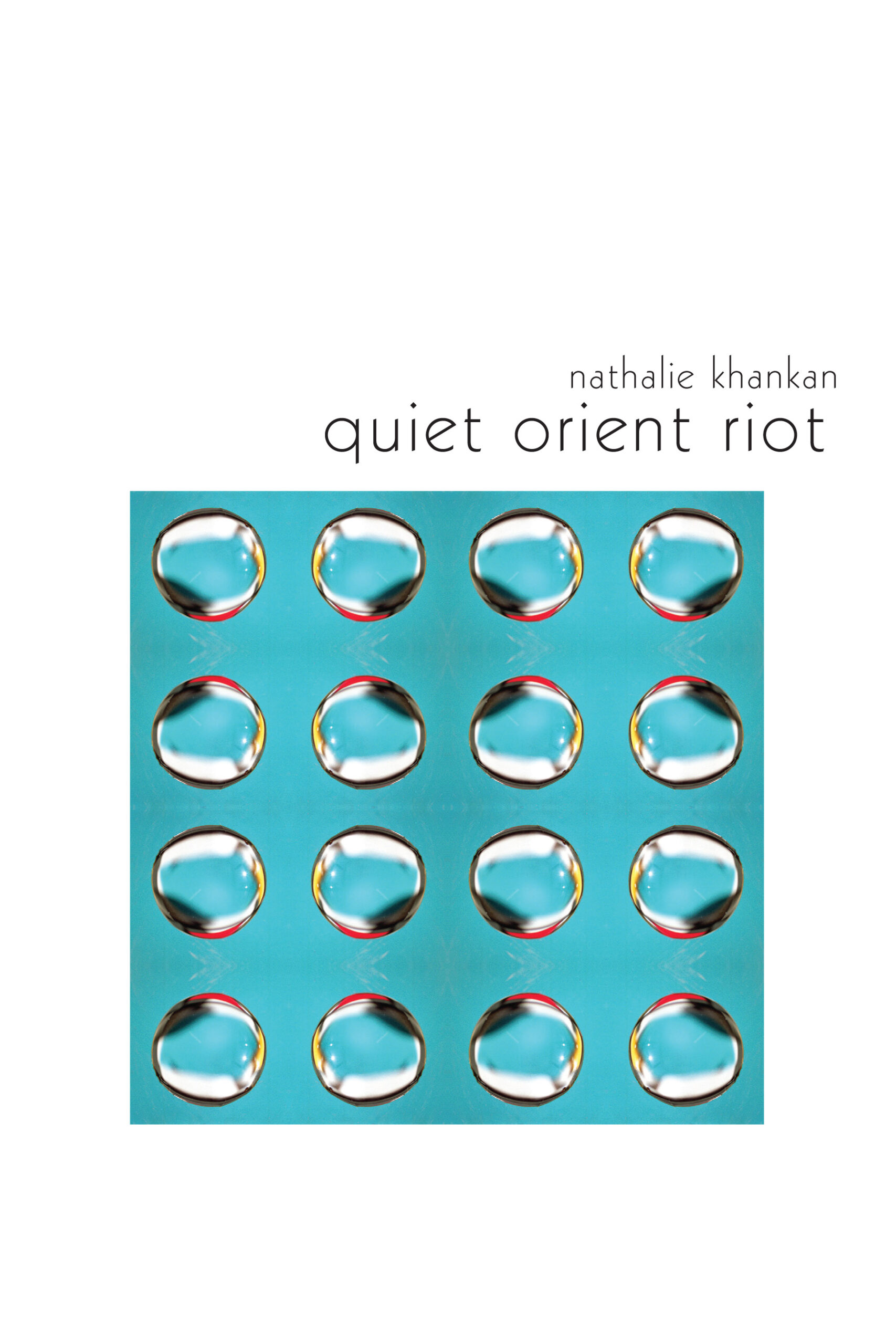

You were instrumental in selecting the cover art for this book. Can you talk about your considerations in your choice of this image, and how it folds into the book’s manifestation in full?

Bashir Makhoul is a Palestinian artist from the Galilee now living in England. I saw One Drop of My Tears at the Palestinian Museum in Birzeit in the West Bank last summer (2019) and was immediately drawn to it. As part of a series, the work sat next to three other photographic works One Centimeter of My Sand, One Grain of My Soil, and One Centimeter of My Blood. Each of them explores questions of identity, ownership, and belonging, and the tension between singularity and repetition. In that sense they fall easily into conversation with the poems in my book.

As it happens, I discovered Bashir’s work in the same month I learned that Omnidawn would publish quiet orient riot. I love the permeable boundary of every single surface tension molecule in One Drop of My Tears. Spare and suggestive, at once melody and muscle, Bashir’s One Drop beautifully amplifies the book’s formal and thematic engagements with repetition and reproduction.