Description

Borrowing the poetic language found in boxing lore and in the Rocky films, Shadowboxing pieces together a poetic portrait of Josefo, a Chicano adolescent working and becoming a poet in the farm territories of Central California. Rios confounds the relationship between author, speaker, and subject within various forms and, at times, across genre. He employs the lyric, the epistle, the dialogue, and various impersonations to challenge the boundaries of what we call poetry or theater and our understanding of high and low culture. He challenges the usefulness of poetry and stands upon oral histories to demystify California’s overlooked labor class. Rios invites the reader to enter Josefo’s world of memory, experience, and talk. It is a world of packinghouse mentors, storytelling grandmothers, parable sharing plumbers, smooth talking truck drivers, and infinitely patient literature professors.

Winner of a 2018 American Book Award

?“Voice” and “epic” are words that are distributed loosely in the poetry world. But I use them with all heat that I can muster. Joseph Rios does for Xican@ poetics what Jean Toomer’s Cane did for the Harlem Renaissance: he radicalizes it into an undeniable modernity. And like Toomer, Rios uses all the genres at his disposal. He uses the epistle, the dramatic dialogue, epigrams from popular culture, and even has a Romantic touch. Pablo Neruda hoped for a poetry that could feed us with the bounty of bread. Rios’ audiences, his carnales, want to know if poetry can fix a broken down Cherokee. That is what the poet, in the shadow of machismo and financial pragmatism, is up against.

FRom the FoRewoRd by willie peRdomo

Shadowboxing: Poems and Impersonations is the most original, charged, exciting debut I have read in years. Joseph Rios redefines fearlessness with a signature talent and unapologetic conviction. The agile flurry of his storytelling is dazzling: Zapata and Lorca, Shakespeare and Borges, Rocky Balboa, family and Tias, and the brown bodies of East Oakland and West Fresno are all part of this dance, this poetry as shadowboxing. This is duende and fire, language as pugilism. This is a new poetics at the next level, part theater, full urgency, fist-waving resistance, memory and homage, with so much vitality and velocity these poems tremor and shake. Trust when the poet writes, “I reach for the dial and discover I can bend the moonlight.” Rios is ahead of the curve. This book is simply brilliant and unforgettable.

lee heRRick

Joseph Rios pulls no aesthetic punches in this knockout debut. Within the ring of each page, Rios throws combinations of lyric, narrative, playwriting, and avant-garde techniques. Despite the originality of this work, it is situated at the crossroads of the Chicano and Fresno poetic traditions (Larry Levis, Philip Levine, Juan Felipe Herrera, Alfred Arteaga, and Jose? Montoya). Throughout, Rios bobs and weaves through many traditions, voices, forms, and languages in order to shadowbox all the unfinished and impersonated versions of the self. After the sixteenth round of this book, the decision is unanimous: the poet goes the distance.

cRaig SantoS peRez

About the Author

Reviews

Excerpt

Joseph Rios was born in Clovis, CA. Joseph’s work has appeared in: Los Angeles Review, Huizache, New Border, Southern Humanities Review, Poets Responding to SB1070, and bozalta. He is a recipient of the John K. Walsh residency fellowship from Notre Dame. Joseph is a VONA alumnus, a Macondo fellow, and a graduate of the University of California, Berkeley. He lives in Los Angeles.

A brief interview with Joseph Rios

(conducted by Gillian Olivia Blythe Hamel)

What a pleasure it is to be publishing Shadowboxing. I was blown away by this book when I came across it in an Omnidawn contest and knew that I wanted us to publish it regardless of the outcome. I’d never read anything quite like its mashup of music, verse, narrative, portrait, all working together to interrogate what is, isn’t, should be poetry. Can you say more about your relationship to form, and how that catalyzed this work?

I think I was trying to re-create my late grandmother’s kitchen table on the page. It’s where everyone would congregate. The table itself was one of those old, oblong, particleboard types that’s covered in a slick plastic floral table cover. It’s where she served me breakfast every morning during elementary school. It’s where she’d deal out solitaire and tell me the same stories over and over again. It’s where the local metiches and busy body señoras would come and sit when they had the best gossip to share. It’s where my grandfather still sits and reads the paper in the morning and where he does his word searches. It’s where we grandchildren would sit late into the night and talk shit. We’d recount old stories, recite movie lines, talk beat samples, and past indiscretions. It’s where we sat before and after funerals, super bowls, birthdays, and after long nights at the bar. I guess what I’m trying to say is that I’m taking all that and doing my best to plug it into poetry. All of it is poetry to me. And I think when we explore the traditions enough, we find ample space for every style, every genre, and every voice we can offer up.

As intoxicatingly irreverent and iconoclastic as this work is, it clearly also has a deep affection for its poetic lineage, from the opening epigraph from Blake to the invocations of theater to the discussion of Lorca and Hemingway that closes the book. The fiery prologue also directly calls out the importance of overtly literary education in disenfranchised communities. I’d love to hear your thoughts on the role of history and tradition for works that seek to elevate and reframe what’s considered literary language.

I love this word you use: affection. So on point. As an undergrad, I left Fresno to study literature at UC Berkeley because I had a deep affection for literature. I’ve had that affection for writing and literature since I was a young kid. I also think I have literary abandonment issues. In the beginning, I felt so out of place at Berkeley. During my first week, I sat in the bathroom stalls between classes. I was terrified. In my English classes, I was one of a few students of color. In those classes we read Chaucer, Milton, Blake, Fielding, and such. And while I later protested outside those same classrooms and got beat up by cops, I never felt like one of those POC writers who says, “Fuck old white man literature.” Like I said, I have literary abandonment issues. I do feel like Latinx/Chicana/o and Latin American authors have been left out of the western and so-called “American” canon but I still have a great affection for a group of texts that I still see as essential and equally mesmerizing as when I first read them. As it is with the important people in our lives, it is complicated to continue to love something or someone who mistreats you, ignores you, or has left you behind all together. It’s ever more difficult to fully divorce ourselves from them. But that’s how I feel about my lineage as it pertains to these “classics.” I continue to love and forgive them even though they can never learn to love me back. Because, you know, they’re dead. The way I avenge them is in my attempts to make them fresh. For instance, I was sitting in poetry class once and I couldn’t get over how much Gertrude Stein was making me think of Luther Vandross. “A chair is still a chair… a room is still a room..” and so on. Boom. That became part of a poem.

I live and write by what Milosz wrote. He asked, What is poetry which does not save nations or people? Blew me away when I read that at 19. Still does. He writes it as if it’s in poetry’s nature to save nations and people. I want the conviction to say shit like that and mean it. The times we live in make it harder and harder to hold that belief. I want to convey the urgency of Milosz and other Polish poets like Zbigniew Herbert, you know? It was partly due to his Cogito that I went forward with my Josefo. There’s a loving essay Larry Levis wrote about Herbert where he plays chauffeur to him in Los Angeles. It’s in a book of Levis’s prose. I re-read it every couple of years. There’s another essay to be written about the Polish poets’ influence on Fresno poetry. File it under: future projects. To your question, I will say that I have always considered myself a poet in-the-tradition. Always. Every poem has a bit of somebody or something else I picked up along the way. Sometimes it’s canonical literature stuff, sometimes it’s just some inside joke I wrote for Javier Huerta. It’s all fair game.

Speaking of tradition, one of the things that initially surprised and excited me about this manuscript was its focus on the oral tradition, and how the perception of our lived experience is filtered through storytelling, anecdote, and collective memory. I’d love to hear you say more about as it relates to the intention of the book as a physical/visual object, and how these two modes coalesce in your work.

These old ladies would always come in the back door unannounced. Always unannounced. Only strangers knocked on the front door, you should know. It’s still that way. These old women would sit with my grandma and talk for hours in a mix of something I can only describe as 1940s farmworker Spanglish. The English sounds like the sing-songy Spanish and the Spanish like their sing-songy English. I’m doing an impersonation of it right now, but you can’t hear me. My grandpa would have said, “Speaking wiri wiri” (See Dan Vera’s book of the same name). Anyway, my grandma would often tell the same stories to different women as each member of our neighborhood social network made its way through the kitchen. I’d be sitting there at the table, small and unassuming, secretly memorizing my grandma’s stories and, more importantly, how she told them and how these ladies reacted to one another, how they leaned in and back, raised their voices, how my grandma would stop dealing out the cards right before she whispered – anything for added emphasis. I took note of it all as if it was some well rehearsed performance. And you know it was.

Some context: Our family has lived on the same corner in Clovis, CA since the mid 1920s. 8th and Dewitt. Right across from the Catholic church. My grandpa was an altar boy there. If you knew him, you’d laugh at that. He’d tell you the best part about altar-boying was the free wine. A lot of our Mexican neighbors have lived there just as long. When we started losing our elders, it became abundantly clear how important my memory of these stories would become. When they die, fewer and fewer of the younger ones can recall their stories. They’re not written down in any history book or recorded on any tapes, though they spent a lifetime giving them away at the any number of kitchen tables like ours. When they go, the stories go. I’ve had to eulogize some pretty important people in my life. My grandmother included. That in mind, I’d say a poet’s highest calling and most enduring charge is to honor and speak for the dead. In this book’s dialogues, I allow some of my dead to speak and I hope to keep some part of them alive to be read and heard for as long as possible.

I’d love for you to talk about any writers, artists, thinkers who have influenced you in this work; in what direct or indirect ways have you felt this influence? And perhaps you could talk about who you’re reading currently? With whom do you feel a kinship, a provocation, a catalyzing relationship of some kind?

Richard Pryor. Pryor is the uncontested king and doesn’t need a young poet to add to his legacy. But as a poet, I devoured everything I could find on him. I watched every clip, every special. I listened to every album, watched damn near every one of his movies. The movies, in particular, missed the mark most times but I don’t think Hollywood ever wrote a role that did him justice. I was lucky enough to take class with Professor Scott Saul, a biographer of his. Saul wrote a well-researched biography of his early life that is a Pryor fan must-read. I became obsessed with his so-called “breakdown” in Vegas and his dormant Berkeley period with Paul Mooney, Ishmael Reed, and KPFA. What interested me most was his awakening there and his insistence on trading in the clean set, the suit, and the conked hair for fearless truth telling. And his impersonations, man. Those voices, those characters he based on people he knew from the block – I loved that shit. I wanted my poetry to do some of that. I wanted to impersonate my people’s voices on the page and I wanted the reader to know them, who they are, and how they sound. I wanted a poetry that didn’t mind if Johnny Carson wouldn’t have it or that Dean Martin was in the audience. It would be the kind of poetry that went out on stage and said, “Fuck it.”

Oh, what am I reading right now? Well, I got a handful of friends with books on the way. I’m looking forward to Vickie Vertiz’s book. The homie Javier Zamora is about to drop one. Gonna be a monster, no doubt. Chiwan Choi’s The Yellow House just fucked me up in the best ways. Best book I read this year. Had me thinking about my teenage years in the church and was reminiscent of Andres Montoya’s first book The Ice Worker Sings. I actually read an early draft of Montoya’s new book, too. Get ready. Not only is Daniel Chacon’s intro heartbreaking, but man, those Leukemia poems broke me right open. My Fresno homegirl Sara Borjas has a manuscript that I’ve read and it’s good as hell. No BS. Just waiting on a publisher there, but it’s only a matter of time. Danez Smith’s Black Movie is dope. You ask about kinships. There’s one that is not afraid of calling on material away from poetry. Had to read it aloud and standing up. I think that’s a mark of good poetry: when you read it, you can’t sit still. You gotta move, gotta standup, take a walk, gotta move, gotta move.

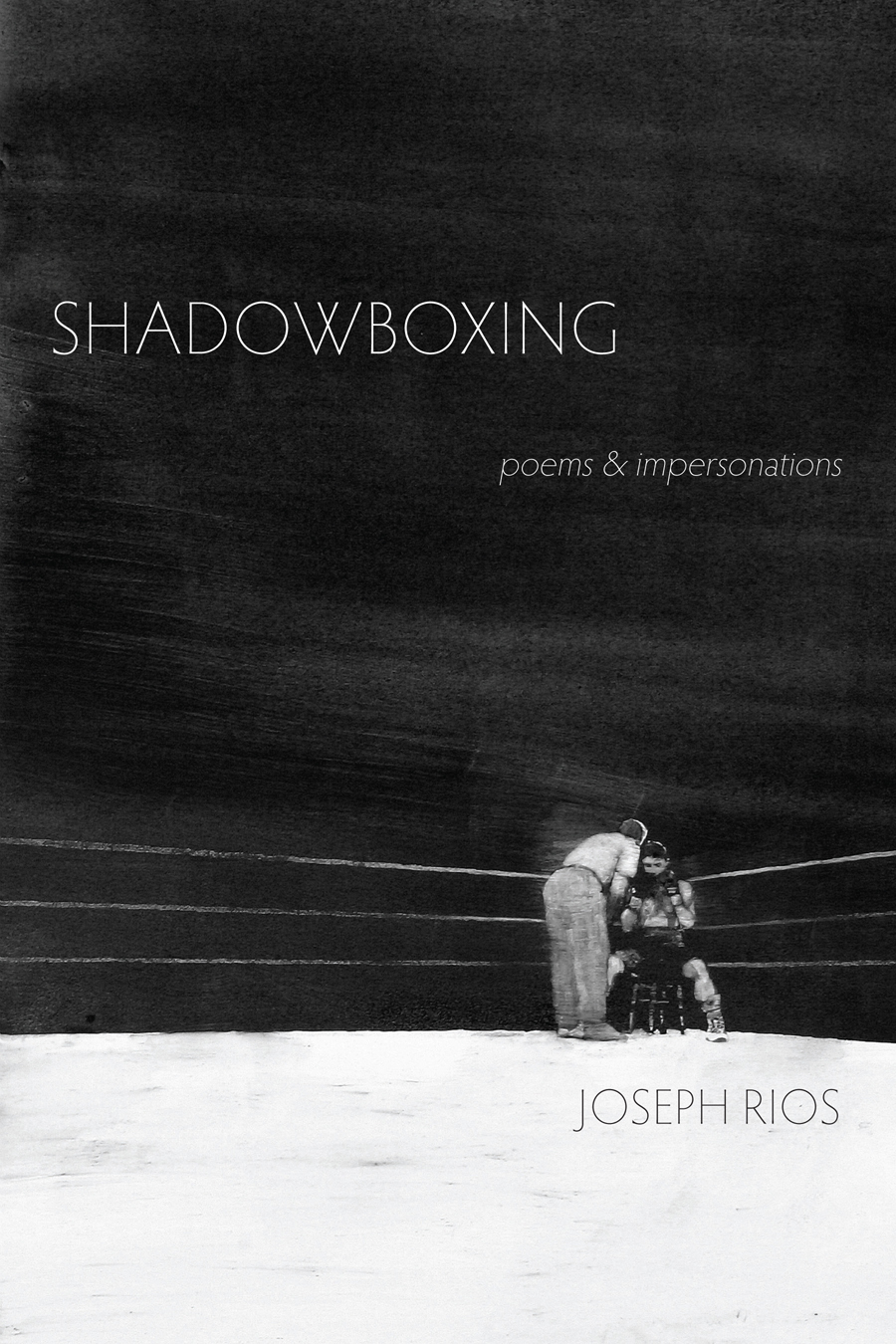

You were instrumental in the selection of the image that is used in the cover design for this book. Would you describe your considerations regarding the cover image? How does this cover align with your intentions for the book?

David Rathman is the artist. I’ve never met him, but I’m so excited to have his work on this cover. So thankful to him. Two years ago I was given a month long residency at the Anderson Center in Red Wing, MN. I have Francisco Aragon and the University of Notre Dame to thank for that. That’s where I sent off my manuscript. I made my way to the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis. I saw Rathman’s pieces there. The paintings have an alive, epic feel to them in person even though the canvases are not large. I was drawn in immediately. I wanted to capture some of that magic in the poems. They do visually what I think the best poems do. I had a similar response to the photography of Rafael Cardenas out in Boyle Heights. I was drawn to this one in particular because it illustrates precisely what I hoped to accomplish in the dialogues. Early on in the drafting of this work, I had a breakthrough when I realized I needed to remove the first person from the poems and direct most of my attention to this Josefo character. It created enough distance for me to really explore certain material that made me uncomfortable or was too close to home. In Josefo’s world, his mentors are constantly speaking to him or at him. They are trying to impart some bit of wisdom; they are trying to teach him something and they are hoping against hope that his young ass listens.

Rios draws readers into a combination coming-of-age story and satire of academic pretension in his audacious debut, writing through the figure of a Chicano adolescent (and, presumably, alter ego), Josefo, in the farming locales of Central California. He evinces palpable fury on behalf of the exploited, yet he never misses an opportunity for a ribald comment: ‘Something’s burning in the house./ Could be Tio’s beard.’

Inspiration: My grandmother’s stories, my grandfather’s stories, the dudes I dug trenches with, the packinghouse where I used to work, wrench turners at my uncle’s airplane shop, jornaleros I picked up at Home Depot in Cypress Park, in Oakland, Marina del Rey, Daly City. My cousin Gabe’s vinyl collection, Dro’s Navy stories, dysfunctional romantic relationships, regret, mistakes, degenerate behavior, survival, and healing. You know, all that stuff you talk about when you and your cousin Erica are drunk and crying at four in the morning. Also, watching people I love get sick and pass away. All that loss, too much loss. Mourning, of course.

As an exuberant collection of relentless declamations against the existing economic order, “Shadowboxing” contains fresh poems of elemental protest, open reflections on politically motivated murders and disappearances, and lyric proclamations praising the inherent superiority of collective identity over the relic of the personal.

Think abouT The fighT

This is the sum of many Sundays

And Eighteen Art Laboe dedications

Never aired in towns called Wasco

Coalinga Sanger McFarland & Fowler

Where we’re taught to be negatively capable

Criminal kil[liminal] Eye tee why

Neither One of Us Ready To Die

Suevecito Gladys Bootsy

War Lighter Shade of

Say It Loud

I’m Brown & I’m Proud

Ask around

(I’m a crate diver’s dream)

[In this place discovery of source

prefaces all understanding]

And besides

(Chitlin’ blues

Women have all the answers)

My brother His open window The cold

highway ninetynine Pink oleander bushes

clipped at the knuckle Dried Blown

Raked swiftly into thirty-two-gallon buckets

Tossed over shoulders into trailer Stomped

under jagged Timbs We must believe the cholo

version of Rapper’s Delight still exists in Dad’s

two-door Honda Accord Wherever that may be