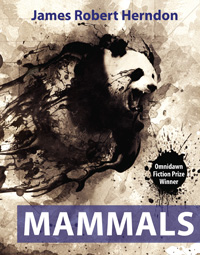

Description

This novel tells of a young man’s attraction and ultimate addiction to skunk musk, and the social difficulties he encounters as a result. He longs to find an isolated utopia where he can experience his addiction in peace, but he is thwarted by all, including a young woman who understands his skunk fetish because she has a fish fetish.

About the Author

Reviews

Excerpt

Justin Courter’s short stories and poems have been published in The Berkeley Fiction Review, Fugue, Many Mountains Moving, Fourteen Hills, The Literary Review, New Orleans Review, LIT, Northwest Review, Pleiades, Main Street Rag, Phantasmagoria, Apalachee Review, North Dakota Review, Pearl and other journals. Skunk: A Love Story is his first published novel. His unpublished novel, Cadenza, was shortlisted for the Graywolf Press S. Mariella Gable Prize, and his short story collection was selected as semi-finalist for the 2003 John Simmons Iowa Short Fiction Award. He lives in New York and works for the Wildlife Conservation Society.

So don’t get put off by the idea of a Casper Milquetoast-type narrator who becomes addicted to skunk musk (the smell reminds him of the beer his alcoholic late mother favored) and finds love (the novel’s subtitle is A Love Story) with a brilliant marine biologist who has bioengineered a solution for global warming and just happens to have a fetish of her own for the smell of fish. Odd, yes, but no more so than the oddity of most human attraction. How many times have you heard the expression, “What does she (or he) see in him (or her)?” In depicting two hygienically-challenged characters who, beyond sharing the status of outcasts, have polar opposite personalities, Courter depicts the elements in the chemistry of love by focusing on somewhat more unusual particles.

Only three years ago did I finally decide to get a skunk of my own. This was after a long, tentative courtship of the skunk scent. If I were driving on a country road and smelled skunk, I immediately pulled over and sat, sometimes for hours, with all the windows rolled down, breathing deeply and letting my thoughts drift among whatever daydreams the scent inspired. I often packed a lunch and devoted my Sunday to one of these drives. But I longed for the pleasure of enjoying the scent of the skunk entirely at my leisure.

By the time I was thirty years old, the notion that I was completely self-sufficient and could do, more or less, what I pleased, began to take shape somewhere in my mind. I had a job as a copywriter for Grund & Greene, a publisher of law books, and I had my own small house in New Essex, a relatively tranquil suburb. I was proud of my house—sad, gray shoe box that it was—with its knee-high hedge, which I kept squarely trimmed, running across the front like a fender. Having scrimped and saved, having lived in tiny, roach-ridden apartments for years, I was at last the owner of something more substantial than the old, smoke-colored Eldorado in which I got around on weekends.

As I am one who has learned to prepare for all of life’s inevitabilities, I built a six-foot fence along the perimeter of my tiny back yard and constructed a hutch about the size of a dog house. Thereafter, several weekends were devoted to tramping around some woods outside town until the day I came across Homer.

It was a crisp autumn afternoon. The sky was a gray sheet of legal bond resume paper upon which were scribbled the leafless branches of maples and birches, and I strode through woods carrying a large burlap sack. When I first spotted Homer, he was rooting around in a pile of dead leaves. Though I tried to approach him stealthily, my feet crunched leaves and snapped twigs. The skunk stopped what he was doing, turned to face me, and sprung suddenly to attention like a puppet on a string. I froze. He arched his back and seemed to grow taller. I took a slow step forward. The little beast hissed, I took a second step, and he began to thump the ground with his forepaws. He became increasingly agitated, gradually raising his plume of a tail until it stood straight up. Then, when I was still about six feet from him, he spun around, quicker than a gunslinger, and sprayed in my direction. He wasn’t a bad shot. The yellow juice he emitted splattered my trousers, and any other predator he could have considered thwarted. Poor fellow. He couldn’t possibly have known that what he was doing was tantamount to slipping an aphrodisiac to a nymphomaniac.

The scent of skunk musk is the richest of all olfactory pleasures. It is a bitter-sweet combination of lilac, tilled earth, McDougal’s beer, dogwood blossoms, apple pie, fresh snow and Moschus—the miniature Himalayan musk deer. And the effect on the mind is astonishing. Skunk musk brings the innocence of childhood, the lasciviousness of adolescence and the wisdom of old age to the surface of one’s consciousness all at once. I sucked Homer’s perfume deep into my lungs. My vision blurred, eyes teared, the burlap sack fell from my hands and I became slightly dizzy. Homer began to mosey off through the forest. I returned to my senses and snatched the bag up from the ground. I simply had to have him. I chased him as he scurried about—under bushes, through piles of leaves—and was able to get the sack over him just as he was about to scoot down a hole at the base of a tree. He writhed around and sprayed more of his delicious scent as I tied a knot at the top of the sack and carried him out of the woods. I placed him beside me on the seat of the car and he continued to wriggle for the first quarter hour of the ride home, at which point he got tired and lay still. I opened the sack in front of the hutch I’d built in the back yard and he moseyed right into his new apartment as if he’d never lived anywhere else. It was then that I decided upon his name. “Welcome home, Homer,” I said. But he ignored the hutch after the first night and dug a hole beneath it the next, so that he only used the floor of the structure I’d built as a roof for his subterranean abode.

There was very nearly what one might call a spring in my step on Monday morning when I left the house to walk to the commuter train. Spending the weekend with Homer had given my life an exciting new dimension. I actually waved at Mrs. Endicott, the annoying old widow who lived next door and who owned a high-strung Chihuahua called Tesa. Mrs. Endicott was retrieving the newspaper from her front yard and Tesa stood at her side yapping at me like a battery-operated toy. Mrs. Endicott liked to talk to me practically whenever I stepped outside, providing me with updates on her children, her grandchildren, her rheumatism and other dull topics. She also badgered me with questions. She asked me who my girlfriend was, when I intended to get married, and so forth.

“Hey, Damien,” she said that morning, waving me over to her. I was embarrassed for her because she was standing there in the middle of her yard in a flower-print housecoat, with pink curlers decorating her head. I walked over to her. “What’s going on in your yard, there?” she asked. Her face was wrinkled like a used paper bag, and her sagging cheeks quivered when she spoke. Tesa continued her yapping throughout our conversation.

“Nothing’s ‘going on,’ Mrs. Endicott,” I said. Of the long list of unpleasant qualities this woman exhibited, her prying nature was the most abhorrent.

“You’ve got a dog now don’t you, a little puppy? That’s good, companionship is good. I’m always saying to Noah, my nephew, you oughta get a nice dog, I says, you need a friend. Living all alone like that makes you crazy. But you,” here Mrs. Endicott jabbed me in the chest with a bony finger and smiled, “you got a good head on your shoulders. I always said you did. Now all you need is a good woman to take care of you.”

I began turning away. I detest being poked and prodded physically or psychologically. Crazy indeed. Mrs. Endicott had told me that she herself had lived alone for the past ten years. “Thank you Mrs. Endicott. I think I’ll be on my way.”

She grabbed my arm and held me there. “The only thing is, Damien, you gotta clean up after a dog. I can smell it over in my yard. Wait.” She pulled me a little closer and sniffed deeply. This caused a most disagreeable racket—snot burbled in her nose and phlegm rattled in her throat. I doubted she’d be able to smell the smoke if she were sitting on a burning sofa. “I’m a little stuffed up,” she said, “but I can even smell it on you now. It’s not good. You take him on walks or train him to go in the far corner of the yard, you hear?” She smiled, peering with her cataract-clouded eyes into my bespectacled ones for a moment, then released my arm. “Run along now, you’ll be late for work,” she said.

As I turned and began to walk away, I noticed that Tesa had stopped yapping. Then I felt her attack from behind. Her tiny teeth slipping from around my ankle, she contented herself by yanking at my pant leg and growling fiercely, as if truly committed to removing my pants. I shook my leg vigorously and was about to give her a good swift kick with my other foot, when Mrs. Endicott called, “That’s enough now Tesa.” Tesa released my pants and stood barking until I’d reached the end of the street. Luckily, she’d put only a few pin holes in my pants. I always wore polyester suits, which I found practical, affordable and quite durable; I owned one blue, one gray and one brown. What did trouble me a bit was that Tesa had put a two-inchlong scratch in the leather of my sturdy brown shoes, the same type I’d worn since I was a boy, and on which I always maintained a flawless, military shine.